Apollo 11 – Enciclopédia do Novo Mundo

[ad_1]

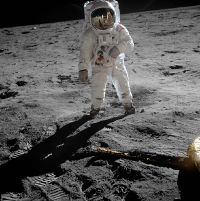

Buzz Aldrin na Lua fotografado |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Da esquerda para a direita: Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, Buzz Aldrin |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Apollo 11 foi o voo espacial que trouxe os humanos à lua pela primeira vez. O Comandante Neil Armstrong e o Piloto do Módulo Lunar Buzz Aldrin formaram a tripulação americana que pousou o Módulo Lunar Apollo. Águia em 20 de julho de 1969 às 20:17 UTC. Armstrong se tornou a primeira pessoa a pôr os pés na superfície lunar seis horas e 39 minutos depois, em 21 de julho às 02:56 UTC; Aldrin juntou-se a ele 19 minutos depois. Eles passaram cerca de duas horas e um quarto juntos fora da espaçonave, coletando 47,5 libras (21,5 kg) de material lunar para trazer de volta à Terra. O piloto do módulo de comando Michael Collins voou no módulo de comando Columbia sozinho na órbita lunar, enquanto na superfície da lua. Armstrong e Aldrin passaram 21 horas e 36 minutos na superfície lunar em um local que chamaram de Base da Tranquilidade antes de decolarem para se encontrar. Columbia em órbita lunar.

A Apollo 11 foi lançada por um foguete Saturn V do Kennedy Space Center em Merritt Island, Flórida, em 16 de julho às 13h32 UTC, e foi a quinta missão tripulada do programa Apollo da NASA. A espaçonave Apollo tinha três partes: um módulo de comando (CM) com uma cabine para os três astronautas, a única parte que retornou à Terra; um módulo de serviço (SM), que suportava o módulo de comando com propulsão, energia elétrica, oxigênio e água; e um módulo lunar (LM) que tinha dois estágios: um estágio de descida para pousar na Lua e um estágio de ascensão para colocar os astronautas de volta na órbita lunar.

Depois de serem enviados à lua pelo terceiro estágio de Saturno V, os astronautas destacaram a espaçonave e viajaram por três dias até entrarem na órbita lunar. Armstrong e Aldrin mudaram-se para Águia e pousou no Mar da Tranquilidade em 20 de julho. Os astronautas usaram Águia‘s estágio de ascensão para decolar da superfície lunar e encontrar Collins no módulo de comando. Eles jogaram Águia antes de realizarem as manobras que impulsionaram Columbia da última de suas 30 órbitas lunares em uma trajetória de volta à Terra.[4] Eles voltaram à Terra e caíram no Oceano Pacífico em 24 de julho, após mais de oito dias no espaço.

O primeiro passo de Armstrong na superfície lunar foi transmitido ao vivo pela televisão para uma audiência mundial. Ele descreveu o evento como “um pequeno passo para [a] cara, um grande salto para a humanidade. “Eric Jones, do Apollo Lunar Surface Journal, explica que o artigo” a “era pretendido, dito ou não; a intenção era contrastar um homem (a ação de um indivíduo) e humanidade (como espécie).[5] A Apollo 11 efetivamente encerrou a corrida espacial e cumpriu um objetivo nacional proposto em 1961 pelo presidente John F. Kennedy: “antes do final desta década, pousar um homem na Lua e devolvê-lo em segurança à Terra. ” O pouso na lua não foi apenas uma fonte de orgulho para os Estados Unidos, mas também para a humanidade. Estima-se que 600 milhões de pessoas assistam ao pouso na lua ao vivo pela televisão em todo o mundo, mais de três vezes a população total dos Estados Unidos em 1969.

Antecedentes históricos

No final dos anos 1950 e início dos anos 1960, os Estados Unidos estavam envolvidos na Guerra Fria, uma rivalidade geopolítica com a União Soviética.[6] Em 4 de outubro de 1957, a União Soviética lançou o Sputnik 1, o primeiro satélite artificial. Este sucesso incrível despertou medos e imaginação em todo o mundo. Demonstrou que a União Soviética tinha a capacidade de lançar armas nucleares em distâncias intercontinentais e desafiou as reivindicações americanas de superioridade militar, econômica e tecnológica.[7] Isso precipitou a crise do Sputnik e deu início à corrida espacial.[8] O presidente Dwight D. Eisenhower respondeu ao desafio do Sputnik criando a Administração Nacional de Aeronáutica e Espaço (NASA) e iniciando o Projeto Mercúrio.[9] que teve como objetivo lançar um homem na órbita da Terra.[10] Mas em 12 de abril de 1961, o cosmonauta soviético Yuri Gagarin se tornou a primeira pessoa no espaço e a primeira a orbitar a Terra. Quase um mês depois, em 5 de maio de 1961, Alan Shepard se tornou o primeiro americano no espaço, completando uma jornada suborbital de 15 minutos. Depois de ser recuperado do Oceano Atlântico, ele recebeu um telefonema de congratulações do sucessor de Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy.[11]

Como a União Soviética possuía veículos lançadores de maior capacidade de içamento, Kennedy escolheu, entre as opções apresentadas pela NASA, um desafio além da capacidade da geração de foguetes existente, para os Estados Unidos e a União Soviética partirem uma posição igual. Uma missão tripulada à Lua serviria a esse propósito.[12]

Em 25 de maio de 1961, Kennedy discursou no Congresso dos Estados Unidos sobre “Necessidades nacionais urgentes” e declarou:

Acredito que esta nação deve se comprometer em alcançar a meta, antes desta década. [1960s] Ele está fora, para pousar um homem na Lua e devolvê-lo em segurança à Terra. Nenhum projeto espacial neste período será mais impressionante para a humanidade ou mais importante para a exploração espacial de longo prazo; e nenhum será tão difícil ou caro de executar. Propomos acelerar o desenvolvimento da espaçonave lunar apropriada. Propomo-nos a desenvolver propelentes alternativos de combustível líquido e sólido, muito maiores do que os atualmente em desenvolvimento, até termos a certeza de qual é superior. Propomos financiamento adicional para o desenvolvimento de outros motores e para a exploração não tripulada, explorações que são particularmente importantes para um propósito que esta nação nunca vai esquecer: a sobrevivência do homem que faz este vôo ousado pela primeira vez. Mas em um sentido muito real, não será um único homem indo para a Lua; se fizermos este julgamento afirmativamente, será uma nação inteira. Porque todos nós temos que trabalhar para colocá-lo lá.[13]

Em 12 de setembro de 1962, Kennedy fez outro discurso para uma multidão de cerca de 40.000 pessoas no estádio de futebol da Universidade Rice em Houston, Texas.[14] Um refrão amplamente citado no meio do discurso é o seguinte:

Ainda não existem lutas nacionais, preconceitos, conflitos no espaço sideral. Seus perigos são hostis a todos nós. Sua conquista merece o melhor de toda a humanidade, e sua oportunidade de cooperação pacífica pode nunca mais se apresentar. Mas por que, dizem alguns, a Lua? Por que escolher isso como nosso objetivo? E você pode perguntar, por que escalar a montanha mais alta? Por que, 35 anos atrás, voar através do Atlântico? Por que Rice joga no Texas?

Nós escolhemos ir à lua! Nós escolhemos ir à lua … Escolhemos ir à Lua nesta década e fazer as outras coisas, não porque são fáceis, mas porque são difíceis; porque essa meta servirá para organizar e medir o melhor de nossas energias e capacidades, porque esse desafio é aquele que estamos dispostos a aceitar, aquele que não estamos dispostos a adiar, e outro que pretendemos vencer, e os demais também.[15]

Apesar disso, o programa proposto enfrentou oposição de muitos americanos, e Norbert Wiener, um matemático do Instituto de Tecnologia de Massachusetts, chamou-o de “monte”.[16] O esforço para levar um homem à Lua já tinha um nome: Projeto Apollo.[17] Quando Kennedy se encontrou com Nikita Khrushchev, o primeiro-ministro da União Soviética em junho de 1961, ele propôs fazer do pouso na lua um projeto conjunto, mas Khrushchev não aceitou a oferta.[18] Kennedy novamente propôs uma expedição conjunta à Lua em um discurso na Assembleia Geral das Nações Unidas em 20 de setembro de 1963.[19] A ideia de uma missão conjunta à Lua foi abandonada após a morte de Kennedy.

Desafios técnicos

Uma decisão inicial e crucial foi escolher o encontro da órbita lunar em vez da ascensão direta e o encontro da órbita terrestre. Um encontro no espaço é uma manobra orbital em que duas espaçonaves navegam pelo espaço e se encontram. Em julho de 1962, o chefe da NASA James Webb anunciou que o ponto de encontro da órbita lunar seria usado.[20] e que a espaçonave Apollo teria três partes principais: um módulo de comando (CM) com uma cabine para os três astronautas, e a única parte que retornava à Terra; um módulo de serviço (SM), que suportava o módulo de comando com propulsão, energia elétrica, oxigênio e água; e um módulo lunar (LM) que tinha dois estágios: um estágio de descida para pousar na Lua e um estágio de ascensão para colocar os astronautas de volta na órbita lunar.[21] Este projeto significava que a espaçonave poderia ser lançada por um único foguete Saturn V que estava em desenvolvimento.[22]

As tecnologias e técnicas necessárias para o Apollo foram desenvolvidas pelo Projeto Gemini.[23] O projeto Apollo foi possível pela adoção da NASA de novos avanços na tecnologia de semicondutores eletrônicos, incluindo transistores de efeito de campo semicondutores de óxido metálico (MOSFETs) na Plataforma de Monitoramento Interplanetário (IMP).[24] e chips de circuito integrado de silício (IC) no computador de orientação Apollo (AGC).[25]

Programa Apollo

O Projeto Apollo foi abruptamente interrompido em sua fase inicial pelo incêndio da Apollo 1 em 27 de janeiro de 1967, no qual os astronautas Gus Grissom, Ed White e Roger B. Chaffee foram mortos. Após uma investigação mais aprofundada, o programa foi reiniciado.[26] Em outubro de 1968, a Apollo 7 avaliou o módulo de comando em órbita terrestre,[27] e em dezembro, a Apollo 8 o testou em órbita lunar.[28] Em março de 1969, a Apollo 9 testou o módulo lunar na órbita da Terra,[29] e em maio, a Apollo 10 conduziu um “ensaio geral” na órbita lunar. Em julho de 1969, tudo estava pronto para que a Apollo 11 desse o último passo em direção à lua.[30]

A União Soviética competiu com os EUA na Corrida Espacial, mas sua liderança inicial foi perdida devido a repetidas falhas no desenvolvimento do lançador N1, que era comparável ao Saturn V.[31] Os soviéticos tentaram vencer os Estados Unidos para devolver o material lunar à Terra usando sondas não tripuladas. Em 13 de julho, três dias antes do lançamento da Apollo 11, a União Soviética lançou o Luna 15, que alcançou a órbita lunar antes da Apollo 11. Durante a descida, um mau funcionamento fez com que o Luna 15 se chocasse com o Mare Crisium. cerca de duas horas antes de Armstrong e Aldrin decolarem da superfície da Lua para iniciar sua jornada para casa. O radiotelescópio nos Laboratórios de Radioastronomia de Nuffield, na Inglaterra, gravou transmissões da Lua 15 durante sua descida, e estas foram lançadas em julho de 2009 para o 40º aniversário da Apollo 11.[32]

Pessoal

A atribuição inicial da tripulação do Comandante Neil Armstrong, do Piloto do Módulo de Comando (CMP) Jim Lovell e do Piloto do Módulo Lunar (LMP) Buzz Aldrin na tripulação reserva da Apollo 9 foi anunciado oficialmente em 20 de novembro de 1967.[33] Lovell e Aldrin haviam voado juntos anteriormente como a tripulação do Gemini 12. Devido a atrasos no projeto e fabricação do LM, Apollo 8 e Apollo 9 trocaram as equipes primária e reserva, e a equipe de Armstrong se tornou a reserva de Apollo 8. Com base no esquema normal de rotação da tripulação, esperava-se que Armstrong comandasse a Apollo 11.[34]

Haveria uma mudança. Michael Collins, Apollo CMP 8 tripulantes, começaram a ter problemas nas pernas. Os médicos diagnosticaram o problema como um crescimento ósseo entre a quinta e a sexta vértebras, que exigia cirurgia.[35] Lovell assumiu seu lugar na Apollo 8 membros da tripulação, e quando Collins se recuperou, ele se juntou à tripulação de Armstrong como CMP. Enquanto isso, Fred Haise serviu como o LMP de backup e Aldrin como o CMP de backup para a Apollo 8.[36] A Apollo 11 foi a segunda missão americana na qual todos os membros da tripulação tinham experiência anterior em voos espaciais. A tripulação da Apollo 10 também tinha experiência anterior. O próximo não foi até o STS-26 em 1988.[4]

Deke Slayton deu a Armstrong a opção de substituir Aldrin por Lovell, pois alguns pensaram que trabalhar com Aldrin era difícil. Armstrong não teve problemas em trabalhar com Aldrin, mas pensou nisso um dia antes de recusar. Ele achava que Lovell merecia comandar sua própria missão (eventualmente Apollo 13).[37]

A tripulação principal da Apollo 11 não tinha a camaradagem próxima e alegre caracterizada pela da Apollo 12. Em vez disso, eles forjaram uma relação de trabalho pessoal. Armstrong em particular era notoriamente distante, mas Collins, que se considerava um solitário, confessou rejeitar as tentativas de Aldrin de criar um relacionamento mais pessoal.[38] Aldrin e Collins descreveram a tripulação como “bons estranhos”.[39] Armstrong discordou da avaliação, dizendo que “todas as equipes em que atuou trabalharam muito bem juntas”.[40]

Preparativos

Seleção de local

O Apollo Site Selection Board da NASA anunciou cinco possíveis locais de pouso em 8 de fevereiro de 1968. Estes foram o resultado de dois anos de estudos baseados em fotografias de alta resolução da superfície lunar pelas cinco sondas não tripuladas. do programa Lunar Orbiter e informações sobre as condições da superfície fornecidas pelo programa Surveyor.[41] Os melhores telescópios terrestres não conseguiam resolver os recursos com a resolução exigida pelo Projeto Apollo.[42] O local de pouso tinha que ser próximo ao equador lunar para minimizar a quantidade de propelente necessária, livre de obstáculos para minimizar as manobras e plano para simplificar a tarefa do radar de pouso. O valor científico não foi levado em consideração.[43]

Áreas que pareciam promissoras em fotos tiradas na Terra eram frequentemente consideradas totalmente inaceitáveis. A exigência original de que o local estivesse livre de crateras teve que ser relaxada, pois nenhum local foi encontrado.[42] Cinco sites foram considerados: Sites 1 e 2 estavam no Mar da Tranquilidade (Mare Tranquilitatis); Local 3 foi em Central Bay (Sinus Medii); e sites 4 e 5 estavam no Oceano de Tempestades (Oceanus procellarum)[41]

A seleção final do site foi baseada em sete critérios:

- O local precisava ser liso, com relativamente poucas crateras;

- com caminhos de aproximação livres de grandes colinas, penhascos altos ou crateras profundas que podem confundir o radar de pouso e fazer com que ele emita leituras incorretas;

- alcançável com uma quantidade mínima de propulsor;

- permitir atrasos na contagem regressiva de lançamento;

- fornecer à espaçonave Apollo um caminho de retorno livre, um que permitiria que ela girasse ao redor da Lua e retornasse com segurança à Terra sem a necessidade de partida do motor, caso surgisse um problema no caminho para a Lua;

- com boa visibilidade durante a aproximação de pouso, o que significa que o Sol estaria entre 7 e 20 graus atrás do LM; Y

- uma inclinação geral de menos de dois graus na área de pouso.

A exigência do ângulo solar era particularmente restritiva, limitando a data de lançamento a um dia por mês.[41] Um pouso logo após o nascer do sol foi escolhido para limitar as temperaturas extremas que os astronautas experimentariam.[44] O site selecionado pelo Apollo Site Selection Board 2, com 3 sites Y 5 como backups caso o lançamento tivesse que ser atrasado. Em maio de 1969, o módulo lunar da Apollo 10 voou a 15 quilômetros (9,3 milhas) do local. 2, e relatou que era aceitável.[45]

Decisão do primeiro passo

Durante a primeira coletiva de imprensa após o anúncio da tripulação da Apollo 11, a primeira pergunta foi: “Qual de vocês, senhores, será o primeiro homem a pôr os pés na superfície lunar?”[46] Slayton disse ao repórter que não tinha se decidido, e Armstrong acrescentou que “não foi baseado no desejo individual”.[47]

Uma das primeiras versões da lista de verificação de saída tinha o piloto do módulo lunar saindo da espaçonave antes do piloto do módulo de comando, o que era consistente com o que havia sido feito em missões anteriores.[48] O comandante nunca havia feito a caminhada no espaço.[49] Os repórteres escreveram no início de 1969 que Aldrin seria o primeiro homem a andar na Lua, e o administrador associado George Mueller disse aos repórteres que ele também seria o primeiro. Aldrin ouviu que Armstrong seria o primeiro porque Armstrong era civil, o que deixou Aldrin furioso. Aldrin tentou persuadir outros pilotos do módulo lunar de que ele deveria ser o primeiro, mas eles responderam com cinismo sobre o que consideraram uma campanha de lobby. Tentando parar o conflito interdepartamental, Slayton disse a Aldrin que Armstrong seria o primeiro desde que ele era o comandante. A decisão foi anunciada em uma entrevista coletiva em 14 de abril de 1969.[50]

Por décadas, Aldrin acreditou que a decisão final foi em grande parte impulsionada pela localização da incubação do módulo lunar. Como os astronautas usavam seus trajes espaciais e a espaçonave era tão pequena, era difícil manobrar para fora da espaçonave. A tripulação tentou uma simulação em que Aldrin deixou a espaçonave primeiro, mas danificou o simulador ao tentar sair. Embora isso tenha sido o suficiente para os planejadores da missão tomarem uma decisão, Aldrin e Armstrong ficaram no escuro sobre a decisão até o final da primavera.[51] Slayton disse a Armstrong que o plano era ele deixar a nave primeiro, se concordasse. Armstrong disse: “Sim, é assim que se faz”.[52]

A mídia acusou Armstrong de exercer a prerrogativa de seu comandante de sair da espaçonave primeiro.[53] Chris Kraft revelou em sua autobiografia de 2001 que Gilruth, Slayton, Low e ele mesmo se encontraram para garantir que Aldrin não fosse o primeiro a andar na lua. Eles argumentaram que a primeira pessoa a andar na Lua deveria ser como Charles Lindbergh, uma pessoa calma e quieta. Eles tomaram a decisão de mudar o plano de vôo para que o comandante fosse o primeiro a sair da espaçonave.[54]

Prélançamento

O estágio de ascensão do módulo lunar LM-5 chegou ao Kennedy Space Center em 8 de janeiro de 1969, seguido pelo estágio de descida quatro dias depois e o Módulo de Comando e Serviço CM-107 em 23 de janeiro.[1] Havia várias diferenças entre o LM-5 e o LM-4 da Apollo 10; O LM-5 tinha uma antena de rádio VHF para facilitar a comunicação com os astronautas durante seu EVA na superfície lunar; um motor de subida mais leve; mais proteção térmica no trem de pouso; e um pacote de experimentos científicos conhecido como Early Apollo Science Experiment Package (EASEP). A única mudança na configuração do módulo de comando foi a remoção de algum isolamento da tampa frontal.[55] Os módulos de comando e serviço foram ancorados em 29 de janeiro e transferidos do Edifício de Operações e Caixa para o Edifício de Montagem de Veículo em 14 de abril.[1]

O terceiro estágio S-IVB do Saturn V AS-506 chegou em 18 de janeiro, seguido pelo segundo estágio S-II em 6 de fevereiro, o primeiro estágio S-IC em 20 de fevereiro e o Saturn V Instrument Unit o 27 de fevereiro. Às 12h30 de 20 de maio, a montagem de 5.443 toneladas (Modelo: Converter / multi2LoffAonSon) partiu do Edifício de Montagem do Veículo no topo da esteira rolante, com destino à Plataforma de Lançamento 39A, parte do Complexo de Lançamento 39 enquanto a Apollo 10 ainda estava a caminho da lua. Um teste de contagem regressiva começou em 26 de junho e foi concluído em 2 de julho. O complexo de lançamento foi iluminado com holofotes na noite de 15 de julho, enquanto o transportador rastreado carregava a estrutura do serviço móvel de volta ao seu estacionamento.[1] Nas primeiras horas da manhã, os tanques de combustível dos estágios S-II e S-IVB foram preenchidos com hidrogênio líquido. O reabastecimento foi concluído três horas antes do lançamento.[56] As operações de lançamento foram parcialmente automatizadas, com 43 programas escritos na linguagem de programação ATOLL.[57]

Slayton acordou a tripulação logo após as 0400, e eles tomaram banho, fizeram a barba e tomaram o tradicional café da manhã pré-voo de filé e ovos com Slayton e a tripulação de apoio. Eles então vestiram seus trajes espaciais e começaram a respirar oxigênio puro. Às 06:30, eles seguiram para o Complexo de Lançamento 39.[58] Haise entrou Columbia cerca de três horas e dez minutos antes do lançamento. Junto com um técnico, ele ajudou Armstrong a se sentar no sofá esquerdo às 06:54. Cinco minutos depois, Collins se juntou a ele e ocupou sua posição no sofá à direita. Finalmente Aldrin entrou, ocupando o sofá central.[56] Haise saiu cerca de duas horas e dez minutos antes do lançamento.[59] A equipe de fechamento lacrou a escotilha e a cabine foi purgada e pressurizada. A equipe de desligamento deixou o complexo de lançamento aproximadamente uma hora antes do horário de lançamento. A contagem regressiva foi automatizada três minutos e vinte segundos antes do horário de lançamento. Mais de 450 pessoas estiveram nos consoles das salas de tiro.[56]

Missão

Lançar e voar para a órbita lunar

Estima-se que um milhão de telespectadores assistiram ao lançamento da Apollo 11 das estradas e praias próximas ao local de lançamento. Os dignitários incluíram o Chefe do Estado-Maior do Exército dos Estados Unidos, General William Westmoreland, quatro membros do gabinete, 19 governadores de estado, 40 prefeitos, 60 embaixadores e 200 congressistas. O vice-presidente Spiro Agnew assistiu ao lançamento com o ex-presidente Lyndon B. Johnson e sua esposa Lady Bird Johnson.[56] Estiveram presentes cerca de 3.500 representantes da mídia.[60] Cerca de dois terços eram dos Estados Unidos; o restante veio de outros 55 países. O lançamento foi transmitido ao vivo em 33 países, com cerca de 25 milhões de telespectadores apenas nos Estados Unidos. Outros milhões em todo o mundo ouviram transmissões de rádio.[56] O presidente Richard Nixon assistiu ao lançamento de seu escritório na Casa Branca com seu oficial de ligação da NASA, o astronauta da Apollo Frank Borman.[61]

O Saturn V AS-506 lançou a Apollo 11 em 16 de julho de 1969 às 13:32:00 UTC (9:32:00 EDT).[1] Aos 13,2 segundos de vôo, o veículo de lançamento começou a rolar em direção ao seu azimute de vôo de 72,058 °. O desligamento completo dos motores do primeiro estágio ocorreu por volta de 2 minutos e 42 segundos de missão, seguidos pela separação do S-IC e a ignição dos motores S-II. Os motores do segundo estágio desligam e separam aproximadamente às 9 minutos e 8 segundos, permitindo a primeira partida do motor S-IVB alguns segundos depois.[4]

A Apollo 11 entrou na órbita da Terra a uma altitude de 100,4 milhas náuticas (185,9 km) por 98,9 milhas náuticas (183,2 km), dentro de doze minutos de vôo. Após uma órbita e meia, um segundo disparo do motor S-IVB empurrou a espaçonave em seu caminho para a Lua com injeção translunar (TLI) ligada às 16:22:13 UTC. Aproximadamente 30 minutos depois, com Collins no assento esquerdo e nos controles, foi realizada a manobra de transposição, docking e extração. Isso envolveu separar Columbia do estágio S-IVB gasto, virando e acasalando com Águia ainda colado ao palco. Depois que o LM foi removido, a espaçonave combinada rumou para a Lua, enquanto o estágio do foguete voou em uma trajetória além da Lua.[4] Isso foi feito para evitar que o terceiro estágio colidisse com a espaçonave, a Terra ou a Lua. Um efeito de estilingue passando ao redor da Lua o lançou em uma órbita ao redor do sol.[62]

Em 19 de julho às 17:21:50 UTC, a Apollo 11 passou atrás da Lua e acionou seu motor de propulsão de serviço para entrar na órbita lunar.[63] Nas trinta órbitas que se seguiram, a tripulação viu vistas passageiras de seu local de pouso no sul do Mar da Tranquilidade, cerca de 19 km a sudoeste da cratera Sabine D. O local foi selecionado em parte porque era caracterizado como relativamente plano. e suave pelos pousadores automatizados Ranger 8 e Surveyor 5 e pela espaçonave de mapeamento Lunar Orbiter e provavelmente não apresentará grandes desafios de pouso ou EVA.[64] Estava localizado a cerca de 25 quilômetros (16 milhas) a sudeste do Surveyor 5 local de pouso e 68 quilômetros (42 milhas) a sudoeste de Ranger Local do acidente de 8.[65]

Descida lunar

Às 12:52:00 UTC de 20 de julho, Aldrin e Armstrong entraram Águia, e os preparativos finais para a descida lunar começaram. Às 17:44:00 Águia separado de Columbia. Collins, apenas a bordo Columbia, inspecionado Águia quando virou à sua frente para se certificar de que o navio não estava danificado e que o trem de pouso estava devidamente implantado.[65] Armstrong exclamou: “O Águia tem asas! ” [66]

Quando a descida começou, Armstrong e Aldrin encontraram-se passando por marcos na superfície dois ou três segundos antes, e relataram que eram “longos”; eles pousariam quilômetros a oeste de seu ponto de destino. Águia ele estava viajando rápido demais. O problema pode ter sido mascons, concentrações de alta massa que podem ter alterado a trajetória. El director de vuelo, Gene Kranz, especuló que podría haber sido el resultado de una presión de aire adicional en el túnel de atraque. O podría haber sido el resultado de Águila‘s maniobra de pirueta.[67]

Cinco minutos después de la quema de descenso, ya 6.000 pies (1.800 m) sobre la superficie de la Luna, la computadora de guía LM (LGC) distrajo a la tripulación con la primera de varias alarmas inesperadas del programa 1201 y 1202. Dentro del Centro de Control de la Misión, el ingeniero informático Jack Garman le dijo al oficial de orientación Steve Bales que era seguro continuar el descenso, y esto fue transmitido a la tripulación. Las alarmas del programa indicaron “desbordamientos ejecutivos”, lo que significa que la computadora de guía no pudo completar todas sus tareas en tiempo real y tuvo que posponer algunas de ellas.[68] Margaret Hamilton, Directora de Programación de Computadoras de Vuelo de Apolo en el Laboratorio Charles Stark Draper del MIT, recordó más tarde:

Culpar a la computadora por los problemas del Apolo 11 es como culpar a la persona que detecta un incendio y llama a los bomberos. En realidad, la computadora fue programada para hacer más que reconocer condiciones de error. Se incorporó al software un conjunto completo de programas de recuperación. La acción del software, en este caso, fue eliminar las tareas de menor prioridad y restablecer las más importantes. La computadora, en lugar de casi forzar un aborto, lo impidió. Si la computadora no hubiera reconocido este problema y hubiera tomado medidas de recuperación, dudo que el Apolo 11 hubiera sido el exitoso aterrizaje en la Luna que fue.[69]

Durante la misión, se diagnosticó la causa de que el interruptor del radar de encuentro estaba en la posición incorrecta, lo que provocó que la computadora procesara los datos de los radares de encuentro y aterrizaje al mismo tiempo.[65] El ingeniero de software Don Eyles concluyó en un documento de la Conferencia de Orientación y Control de 2005 que el problema se debía a un error de diseño de hardware visto anteriormente durante las pruebas del primer LM sin tripulación en Apollo 5. Tener el radar de encuentro encendido (por lo que se calentó en caso de un aborto de aterrizaje de emergencia) debería haber sido irrelevante para la computadora, pero una desajuste de fase eléctrica entre dos partes del sistema de radar de encuentro podría hacer que la antena estacionaria parezca que la computadora fluctúa hacia adelante y hacia atrás entre dos posiciones, dependiendo de cómo el hardware encendido aleatoriamente. El robo de ciclo adicional espurio, cuando el radar de encuentro actualizó un contador involuntario, provocó las alarmas de la computadora.

Aterrizaje

Cuando Armstrong volvió a mirar hacia afuera, vio que el objetivo de aterrizaje de la computadora estaba en un área sembrada de rocas al norte y al este de un cráter Template: Convert / LoffAoffDbSmid (que luego se determinó que era el cráter West), por lo que tomó el control semiautomático.[70][71] Armstrong consideró aterrizar cerca del campo de rocas para poder recolectar muestras geológicas de él, pero no pudo porque su velocidad horizontal era demasiado alta. Durante el descenso, Aldrin pidió datos de navegación a Armstrong, que estaba ocupado pilotando Águila. Ahora a 107 pies (33 m) sobre la superficie, Armstrong sabía que su suministro de propulsor estaba disminuyendo y estaba decidido a aterrizar en el primer lugar posible de aterrizaje.[72]

Armstrong encontró un terreno despejado y maniobró la nave espacial hacia él. A medida que se acercaba, ahora a 76 m (250 pies) sobre la superficie, descubrió que su nuevo lugar de aterrizaje tenía un cráter. Limpió el cráter y encontró otra parcela de terreno llano. Ahora estaban a 100 pies (30 m) de la superficie, y solo quedaban 90 segundos de propulsor. El polvo lunar levantado por el motor del LM comenzó a afectar su capacidad para determinar el movimiento de la nave espacial. Algunas rocas grandes sobresalieron de la nube de polvo, y Armstrong se centró en ellas durante su descenso para poder determinar la velocidad de la nave espacial.[73]

Una luz informó a Aldrin que al menos una de las sondas de 67 pulgadas (170 cm) que colgaban de Águilaes unas almohadillas habían tocado la superficie unos momentos antes del aterrizaje y dijo: “¡Luz de contacto!” Se suponía que Armstrong apagaba inmediatamente el motor, ya que los ingenieros sospechaban que la presión causada por el propio escape del motor que se reflejaba en la superficie lunar podía hacer que explotara, pero se olvidó. Tres segundos después Águila aterrizó y Armstrong apagó el motor.[74] Aldrin dijo inmediatamente: “Está bien, pare el motor. ACA, fuera de detención”. Armstrong reconoció: “Fuera de detención. Auto”. Aldrin continuó: “Control de modo, ambos automáticos. Anulación del comando del motor de descenso desactivado. Brazo del motor, apagado. 413 está adentro”.[75]

ACA era el conjunto de control de actitud, la palanca de control del LM. La salida fue al LGC para ordenar a los jets del sistema de control de reacción (RCS) que dispararan. “Fuera de detención” significaba que la palanca se había alejado de su posición central; estaba centrado en un resorte como el intermitente de un automóvil. La dirección LGC 413 contenía la variable que indicaba que el LM había aterrizado.

Águila aterrizó a las 20:17:40 UTC el domingo 20 de julio con 216 libras (98 kg) de combustible utilizable restantes. La información disponible para la tripulación y los controladores de la misión durante el aterrizaje mostró que el LM tenía suficiente combustible para otros 25 segundos de vuelo motorizado antes de que un aborto sin aterrizaje se hubiera vuelto inseguro.[4] pero el análisis posterior a la misión mostró que la cifra real probablemente se acercaba a los 50 segundos.[76] El Apolo 11 aterrizó con menos combustible que la mayoría de las misiones posteriores, y los astronautas encontraron una advertencia prematura de bajo combustible. Más tarde se descubrió que esto era el resultado de un ‘chapoteo’ del propulsor mayor de lo esperado, descubriendo un sensor de combustible. En misiones posteriores, se agregaron deflectores anti-salpicaduras adicionales a los tanques para evitar esto.

Armstrong reconoció que Aldrin completó la lista de verificación posterior al aterrizaje con “El brazo del motor está apagado”, antes de responder al CAPCOM, Charles Duke, con las palabras, “Houston, aquí la base de la tranquilidad. Águila ha aterrizado “. El cambio no ensayado de Armstrong de la señal de llamada de” Eagle “a” Tranquility Base “enfatizó a los oyentes que el aterrizaje fue completo y exitoso. Duke pronunció mal su respuesta mientras expresaba el alivio en Mission Control:” Roger, Twan, Tranquility, we copiarte en el suelo. Tienes un montón de chicos a punto de ponerse azules. Estamos respirando de nuevo. Thanks a lot.”[77]

Two and a half hours after landing, before preparations began for the EVA, Aldrin radioed to Earth:

This is the LM pilot. I’d like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening in, whoever and wherever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours and to give thanks in his or her own way.[78]

He then took communion privately. At this time NASA was still fighting a lawsuit brought by atheist Madalyn Murray O’Hair (who had objected to the Apollo 8 crew reading from the Book of Genesis) demanding that their astronauts refrain from broadcasting religious activities while in space. As such, Aldrin chose to refrain from directly mentioning taking communion on the Moon. Aldrin was an elder at the Webster Presbyterian Church, and his communion kit was prepared by the pastor of the church, Dean Woodruff. Webster Presbyterian possesses the chalice used on the Moon and commemorates the event each year on the Sunday closest to July 20.[79] The schedule for the mission called for the astronauts to follow the landing with a five-hour sleep period, but they chose to begin preparations for the EVA early, thinking they would be unable to sleep.[65]

Lunar surface operations

Preparations for Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to walk on the Moon began at 23:43.[4] These took longer than expected; three and a half hours instead of two. During training on Earth, everything required had been neatly laid out in advance, but on the Moon the cabin contained a large number of other items as well, such as checklists, food packets, and tools.[65] Six hours and thirty-nine minutes after landing Armstrong and Aldrin were ready to go outside, and Eagle was depressurized.[80]

Eagle‘s hatch was opened at 02:39:33.[4] Armstrong initially had some difficulties squeezing through the hatch with his portable life support system (PLSS).[81] Some of the highest heart rates recorded from Apollo astronauts occurred during LM egress and ingress.[82] At 02:51 Armstrong began his descent to the lunar surface. The remote control unit on his chest kept him from seeing his feet. Climbing down the nine-rung ladder, Armstrong pulled a D-ring to deploy the modular equipment stowage assembly (MESA) folded against Eagle‘s side and activate the TV camera.[5]

Apollo 11 used slow-scan television (TV) incompatible with broadcast TV, so it was displayed on a special monitor, and a conventional TV camera viewed this monitor, significantly reducing the quality of the picture.[83] The signal was received at Goldstone in the United States, but with better fidelity by Honeysuckle Creek Tracking Station near Canberra in Australia. Minutes later the feed was switched to the more sensitive Parkes radio telescope in Australia.[84] Despite some technical and weather difficulties, ghostly black and white images of the first lunar EVA were received and broadcast to at least 600 million people on Earth.[84] Copies of this video in broadcast format were saved and are widely available, but recordings of the original slow scan source transmission from the lunar surface were likely destroyed during routine magnetic tape re-use at NASA.

While still on the ladder, Armstrong uncovered a plaque mounted on the LM descent stage bearing two drawings of Earth (of the Western and Eastern Hemispheres), an inscription, and signatures of the astronauts and President Nixon. The inscription read:

Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the Moon July 1969, A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.

At the behest of the Nixon administration to add a reference to God, NASA included the vague date as a reason to include A.D., which stands for Anno Domini, “in the year of our Lord” (although it should have been placed before the year, not after).[85]

After describing the surface dust as “very fine-grained” and “almost like a powder”, at 02:56:15,[86] six and a half hours after landing, Armstrong stepped off Eagle‘s footpad and declared: “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.”[4][87]

Armstrong intended to say “That’s one small step for a man”, but the word “a” is not audible in the transmission, and thus was not initially reported by most observers of the live broadcast. When later asked about his quote, Armstrong said he believed he said “for a man”, and subsequent printed versions of the quote included the “a” in square brackets. One explanation for the absence may be that his accent caused him to slur the words “for a” together; another is the intermittent nature of the audio and video links to Earth, partly because of storms near Parkes Observatory. More recent digital analysis of the tape claims to reveal the “a” may have been spoken but obscured by static.[88][89]

About seven minutes after stepping onto the Moon’s surface, Armstrong collected a contingency soil sample using a sample bag on a stick. He then folded the bag and tucked it into a pocket on his right thigh. This was to guarantee there would be some lunar soil brought back in case an emergency required the astronauts to abandon the EVA and return to the LM.[90] Twelve minutes after the sample was collected,[4] he removed the TV camera from the MESA and made a panoramic sweep, then mounted it on a tripod. The TV camera cable remained partly coiled and presented a tripping hazard throughout the EVA. Still photography was accomplished with a Hasselblad camera which could be operated hand held or mounted on Armstrong’s Apollo space suit.[65] Aldrin joined Armstrong on the surface. He described the view with the simple phrase: “Magnificent desolation.”

Armstrong said moving in the lunar gravity, one-sixth of Earth’s, was “even perhaps easier than the simulations … It’s absolutely no trouble to walk around.” Aldrin joined him on the surface and tested methods for moving around, including two-footed kangaroo hops. The PLSS backpack created a tendency to tip backward, but neither astronaut had serious problems maintaining balance. Loping became the preferred method of movement. The astronauts reported that they needed to plan their movements six or seven steps ahead. The fine soil was quite slippery. Aldrin remarked that moving from sunlight into Eagle‘s shadow produced no temperature change inside the suit, but the helmet was warmer in sunlight, so he felt cooler in shadow. The MESA failed to provide a stable work platform and was in shadow, slowing work somewhat. As they worked, the moonwalkers kicked up gray dust which soiled the outer part of their suits.[65]

The astronauts planted the Lunar Flag Assembly containing a flag of the United States on the lunar surface, in clear view of the TV camera. Aldrin remembered, “Of all the jobs I had to do on the Moon the one I wanted to go the smoothest was the flag raising.”[91] But the astronauts struggled with the telescoping rod and could only jam the pole a couple of inches (5 cm) into the hard lunar surface. Aldrin was afraid it might topple in front of TV viewers. But he gave “a crisp West Point salute.”[91] Before Aldrin could take a photo of Armstrong with the flag, President Richard Nixon spoke to them through a telephone-radio transmission which Nixon called “the most historic phone call ever made from the White House.”[92] Nixon originally had a long speech prepared to read during the phone call, but Frank Borman, who was at the White House as a NASA liaison during Apollo 11, convinced Nixon to keep his words brief.[93]

Nixon: Hello, Neil and Buzz. I’m talking to you by telephone from the Oval Room at the White House. And this certainly has to be the most historic telephone call ever made. I just can’t tell you how proud we all are of what you’ve done. For every American, this has to be the proudest day of our lives. And for people all over the world, I am sure they too join with Americans in recognizing what an immense feat this is. Because of what you have done, the heavens have become a part of man’s world. And as you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquility, it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to Earth. For one priceless moment in the whole history of man, all the people on this Earth are truly one: one in their pride in what you have done, and one in our prayers that you will return safely to Earth.

Armstrong: Thank you, Mr. President. It’s a great honor and privilege for us to be here, representing not only the United States, but men of peace of all nations, and with interest and curiosity, and men with a vision for the future. It’s an honor for us to be able to participate here today.[94]

They deployed the EASEP, which included a passive seismic experiment package used to measure moonquakes and a retroreflector array used for the lunar laser ranging experiment. Then Armstrong walked 196 feet (60 m) from the LM to snap photos at the rim of Little West Crater while Aldrin collected two core samples. He used the geologist’s hammer to pound in the tubes—the only time the hammer was used on Apollo 11—but was unable to penetrate more than 6 inches (15 cm) deep. The astronauts then collected rock samples using scoops and tongs on extension handles. Many of the surface activities took longer than expected, so they had to stop documenting sample collection halfway through the allotted 34 minutes. Aldrin shoveled 6 kilograms (13 lb) of soil into the box of rocks in order to pack them in tightly.[95] Two types of rocks were found in the geological samples: basalt and breccia. Three new minerals were discovered in the rock samples collected by the astronauts: armalcolite, tranquillityite, and pyroxferroite. Armalcolite was named after Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins. All have subsequently been found on Earth.[96]

Mission Control used a coded phrase to warn Armstrong his metabolic rates were high, and that he should slow down. He was moving rapidly from task to task as time ran out. As metabolic rates remained generally lower than expected for both astronauts throughout the walk, Mission Control granted the astronauts a 15-minute extension.[97] In a 2010 interview, Armstrong explained that NASA limited the first moonwalk’s time and distance because there was no empirical proof of how much cooling water the astronauts’ PLSS backpacks would consume to handle their body heat generation while working on the Moon.[98]

Lunar ascent

Aldrin entered Eagle primero. With some difficulty the astronauts lifted film and two sample boxes containing 21.55 kilograms (47.5 lb) of lunar surface material to the LM hatch using a flat cable pulley device called the Lunar Equipment Conveyor (LEC). This proved to be an inefficient tool, and later missions preferred to carry equipment and samples up to the LM by hand. Armstrong reminded Aldrin of a bag of memorial items in his sleeve pocket, and Aldrin tossed the bag down. Armstrong then jumped onto the ladder’s third rung, and climbed into the LM. After transferring to LM life support, the explorers lightened the ascent stage for the return to lunar orbit by tossing out their PLSS backpacks, lunar overshoes, an empty Hasselblad camera, and other equipment. The hatch was closed again at 05:11:13. They then pressurized the LM and settled down to sleep.[99]

Presidential speech writer William Safire had prepared an In Event of Moon Disaster announcement for Nixon to read in the event the Apollo 11 astronauts were stranded on the Moon.[100] The remarks were in a memo from Safire to Nixon’s White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman, in which Safire suggested a protocol the administration might follow in reaction to such a disaster.[101][102] According to the plan, Mission Control would “close down communications” with the LM, and a clergyman would “commend their souls to the deepest of the deep” in a public ritual likened to burial at sea. The last line of the prepared text contained an allusion to Rupert Brooke’s First World War poem, “The Soldier”.

While moving inside the cabin, Aldrin accidentally damaged the circuit breaker that would arm the main engine for lift off from the Moon. There was a concern this would prevent firing the engine, stranding them on the Moon. A felt-tip pen was sufficient to activate the switch; had this not worked, the LM circuitry could have been reconfigured to allow firing the ascent engine.

After more than 211⁄dois hours on the lunar surface, in addition to the scientific instruments, the astronauts left behind: an Apollo 1 mission patch in memory of astronauts Roger Chaffee, Gus Grissom, and Edward White, who died when their command module caught fire during a test in January 1967; two memorial medals of Soviet cosmonauts Vladimir Komarov and Yuri Gagarin, who died in 1967 and 1968 respectively; a memorial bag containing a gold replica of an olive branch as a traditional symbol of peace; and a silicon message disk carrying the goodwill statements by Presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon along with messages from leaders of 73 countries around the world.[103] The disk also carries a listing of the leadership of the US Congress, a listing of members of the four committees of the House and Senate responsible for the NASA legislation, and the names of NASA’s past and present top management.[104]

After about seven hours of rest, the crew was awakened by Houston to prepare for the return flight. Two and a half hours later, at 17:54:00 UTC, they lifted off in Eagle‘s ascent stage to rejoin Collins aboard Columbia in lunar orbit.[4] Film taken from the LM ascent stage upon liftoff from the Moon reveals the American flag, planted some 25 feet (8 m) from the descent stage, whipping violently in the exhaust of the ascent stage engine. Aldrin looked up in time to witness the flag topple: “The ascent stage of the LM separated … I was concentrating on the computers, and Neil was studying the attitude indicator, but I looked up long enough to see the flag fall over.”[105] Subsequent Apollo missions planted their flags farther from the LM.[106]

Return

Eagle rendezvoused with Columbia at 21:24 UTC on July 21, and the two docked at 21:35. Eagle‘s ascent stage was jettisoned into lunar orbit at 23:41.[4] Just before the Apollo 12 flight, it was noted that Eagle was still likely to be orbiting the Moon. Later NASA reports mentioned that Eagle‘s orbit had decayed, resulting in it impacting in an “uncertain location” on the lunar surface.[107]

On July 23, the last night before splashdown, the three astronauts made a television broadcast in which Collins commented:

The Saturn V rocket which put us in orbit is an incredibly complicated piece of machinery, every piece of which worked flawlessly … We have always had confidence that this equipment will work properly. All this is possible only through the blood, sweat, and tears of a number of people … All you see is the three of us, but beneath the surface are thousands and thousands of others, and to all of those, I would like to say, “Thank you very much.”[105]

Aldrin added:

This has been far more than three men on a mission to the Moon; more, still, than the efforts of a government and industry team; more, even, than the efforts of one nation. We feel that this stands as a symbol of the insatiable curiosity of all mankind to explore the unknown … Personally, in reflecting on the events of the past several days, a verse from Psalms comes to mind. “When I consider the heavens, the work of Thy fingers, the Moon and the stars, which Thou hast ordained; What is man that Thou art mindful of him?”[105][108]

Armstrong concluded:

The responsibility for this flight lies first with history and with the giants of science who have preceded this effort; next with the American people, who have, through their will, indicated their desire; next with four administrations and their Congresses, for implementing that will; and then, with the agency and industry teams that built our spacecraft, the Saturn, the Columbia, the Eagle, and the little EMU, the spacesuit and backpack that was our small spacecraft out on the lunar surface. We would like to give special thanks to all those Americans who built the spacecraft; who did the construction, design, the tests, and put their hearts and all their abilities into those craft. To those people tonight, we give a special thank you, and to all the other people that are listening and watching tonight, God bless you. Good night from Apollo 11.[105]

On the return to Earth, a bearing at the Guam tracking station failed, potentially preventing communication on the last segment of the Earth return. A regular repair was not possible in the available time but the station director, Charles Force, had his ten-year-old son Greg use his small hands to reach into the housing and pack it with grease. Greg was later thanked by Armstrong.[109]

Splashdown and quarantine

Before dawn on July 24, Hornet launched four Sea King helicopters and three Grumman E-1 Tracers. Two of the E-1s were designated as “air boss” while the third acted as a communications relay aircraft. Two of the Sea Kings carried divers and recovery equipment. The third carried photographic equipment, and the fourth carried the decontamination swimmer and the flight surgeon.[65] At 16:44 UTC (05:44 local time) Columbia‘s drogue parachutes were deployed. This was observed by the helicopters. Seven minutes later Columbia struck the water forcefully 2,660 km (1,440 nmi) east of Wake Island, 380 km (210 nmi) south of Johnston Atoll, and 24 km (13 nmi) from Hornet,[4] with 6 feet (1.8 m) seas and winds at 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) from the east were reported under broken clouds at 1,500 feet (460 m) with visibility of nmi at the recovery site.[110] Reconnaissance aircraft flying to the original splashdown location reported the conditions Brandli and Houston had predicted.[111]

During splashdown, Columbia landed upside down but was righted within ten minutes by flotation bags activated by the astronauts.[65] A diver from the Navy helicopter hovering above attached a sea anchor to prevent it from drifting.[112] More divers attached flotation collars to stabilize the module and positioned rafts for astronaut extraction.[113]

The divers then passed biological isolation garments (BIGs) to the astronauts, and assisted them into the life raft. The possibility of bringing back pathogens from the lunar surface was considered remote, but NASA took precautions at the recovery site. The astronauts were rubbed down with a sodium hypochlorite solution and Columbia wiped with Betadine to remove any lunar dust that might be present. The astronauts were winched on board the recovery helicopter. BIGs were worn until they reached isolation facilities on board Hornet. The raft containing decontamination materials was intentionally sunk.[65]

After touchdown on Hornet at 17:53 UTC, the helicopter was lowered by the elevator into the hangar bay, where the astronauts walked the 30 feet (9.1 m) to the Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF), where they would begin the Earth-based portion of their 21 days of quarantine.[114] This practice would continue for two more Apollo missions, Apollo 12 and Apollo 14, before the Moon was proven to be barren of life, and the quarantine process dropped.[115] Nixon welcomed the astronauts back to Earth. He told them: “As a result of what you’ve done, the world has never been closer together before.”[116]

After Nixon departed, Hornet was brought alongside the 5-short-ton (Template:Convert/t LT) Columbia, which was lifted aboard by the ship’s crane, placed on a dolly and moved next to the MQF. It was then attached to the MQF with a flexible tunnel, allowing the lunar samples, film, data tapes and other items to be removed. Hornet returned to Pearl Harbor, where the MQF was loaded onto a Lockheed C-141 Starlifter and airlifted to the Manned Spacecraft Center. The astronauts arrived at the Lunar Receiving Laboratory at 10:00 UTC on July 28. Columbia was taken to Ford Island for deactivation, and its pyrotechnics made safe. It was then taken to Hickham Air Force Base, from whence it was flown to Houston in a Douglas C-133 Cargomaster, reaching the Lunar Receiving Laboratory on July 30.[65]

In accordance with the Extra-Terrestrial Exposure Law, a set of regulations promulgated by NASA on July 16 to codify its quarantine protocol,[117] the astronauts continued in quarantine. After three weeks in confinement (first in the Apollo spacecraft, then in their trailer on Hornet, and finally in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory), the astronauts were given a clean bill of health.[118] On August 10, 1969, the Interagency Committee on Back Contamination met in Atlanta and lifted the quarantine on the astronauts, on those who had joined them in quarantine (NASA physician William Carpentier and MQF project engineer John Hirasaki),[119] and on Columbia itself. Loose equipment from the spacecraft remained in isolation until the lunar samples were released for study. [120]

Celebrations

On August 13, the three astronauts rode in ticker-tape parades in their honor in New York and Chicago, with an estimated six million attendees.[121] On the same evening in Los Angeles there was an official state dinner to celebrate the flight, attended by members of Congress, 44 governors, the Chief Justice of the United States, and ambassadors from 83 nations at the Century Plaza Hotel. Nixon and Agnew honored each astronaut with a presentation of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[122]

The three astronauts spoke before a joint session of Congress on September 16, 1969. They presented two US flags, one to the House of Representatives and the other to the Senate, that they had carried with them to the surface of the Moon.[123] The flag of American Samoa on Apollo 11 is on display at the Jean P. Haydon Museum in Pago Pago, the capital of American Samoa.[124]

This celebration began a 38-day world tour that brought the astronauts to 22 foreign countries and included visits with the leaders of many countries.[125] The crew toured from September 29 to November 5.[126][127] Many nations honored the first human Moon landing with special features in magazines or by issuing Apollo 11 commemorative postage stamps or coins.[128]

Legado

Cultural significance

Humans walking on the Moon and returning safely to Earth accomplished Kennedy’s goal set eight years earlier. In Mission Control during the Apollo 11 landing, Kennedy’s speech flashed on the screen, followed by the words “TASK ACCOMPLISHED, July 1969.” The success of Apollo 11 demonstrated the United States’ technological superiority;[129] and with the success of Apollo 11, America had won the Space Race.[130]

Twenty percent of the world’s population watched humans walk on the Moon for the first time. While Apollo 11 sparked the interest of the world, the follow-on Apollo missions did not hold the interest of the nation. One possible explanation was the shift in complexity. Landing someone on the Moon was an easy goal to understand; lunar geology was too abstract for the average person. Another is that Kennedy’s goal of landing humans on the Moon had already been accomplished.[131] A well-defined objective helped Project Apollo accomplish its goal, but after it was completed it was hard to justify continuing the lunar missions.[132]

While most Americans were proud of their nation’s achievements in space exploration, only once during the late 1960s did the Gallup Poll indicate that a majority of Americans favored “doing more” in space as opposed to “doing less”. By 1973, 59 percent of those polled favored cutting spending on space exploration. The Space Race had ended, and Cold War tensions were easing as the US and Soviet Union entered the era of détente. This was also a time when inflation was rising, which put pressure on the government to reduce spending. What saved the space program was that it was one of the few government programs that had achieved something great. Drastic cuts, warned Caspar Weinberger, the deputy director of the Office of Management and Budget, might send a signal that “our best years are behind us”.[133]

After the Apollo 11 mission, officials from the Soviet Union said landing humans on the Moon was dangerous and unnecessary. At the time the Soviet Union was attempting to retrieve lunar samples robotically. The Soviets publicly denied there was a race to the Moon, and indicated they were not making an attempt.[134] Mstislav Keldysh said in July 1969, “We are concentrating wholly on the creation of large satellite systems.” It was revealed in 1989 that the Soviets had tried to send people to the Moon, but were unable due to technological difficulties.[135] The public’s reaction in the Soviet Union was mixed. The Soviet government limited the release of information about the lunar landing, which affected the reaction. A portion of the populace did not give it any attention, and another portion was angered by it.[136]

The Apollo 11 landing is referenced in the songs “Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins” by The Byrds on the 1969 album Ballad of Easy Rider and “Coon on the Moon” by Howlin’ Wolf on the 1973 album The Back Door Wolf.

Spacecraft

The Command Module Columbia went on a tour of the United States, visiting 49 state capitals, the District of Columbia, and Anchorage, Alaska.Allan Needel, “The Last Time the Command Module Columbia Toured”, https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/last-time-command-module-columbia-toured, Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, February 25, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2020}} In 1971, it was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution, and was displayed at the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) in Washington, DC. It was in the central Milestones of Flight exhibition hall in front of the Jefferson Drive entrance, sharing the main hall with other pioneering flight vehicles such as the Wright Flyer, Spirit of St. Louis, Bell X-1, North American X-15 and Friendship 7.[137]

Columbia was moved in 2017 to the NASM Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, to be readied for a four-city tour titled Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission. This included Space Center Houston from October 14, 2017 to March 18, 2018, the Saint Louis Science Center from April 14 to September 3, 2018, the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh from September 29, 2018 to February 18, 2019,its last location at Seattle’s Museum of Flight from March 16 to September 2, 2019.[138][139] Continued renovations at the Smithsonian allowed time for an additional stop for the capsule, and it was moved to the Cincinnati Museum Center. The ribbon cutting ceremony was on September 29, 2019.[140]

The descent stage of the LM Eagle remains on the Moon. In 2009, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) imaged the various Apollo landing sites on the surface of the Moon, for the first time with sufficient resolution to see the descent stages of the lunar modules, scientific instruments, and foot trails made by the astronauts.[141] The remains of the ascent stage lie at an unknown location on the lunar surface, after being abandoned and impacting the Moon. The location is uncertain because Eagle ascent stage was not tracked after it was jettisoned, and the lunar gravity field is sufficiently non-uniform to make the orbit of the spacecraft unpredictable after a short time.[142]

In March 2012 a team of specialists financed by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos located the F-1 engines from the S-IC stage that launched Apollo 11 into space. They were found on the Atlantic seabed using advanced sonar scanning.[143] His team brought parts of two of the five engines to the surface. In July 2013, a conservator discovered a serial number under the rust on one of the engines raised from the Atlantic, which NASA confirmed was from Apollo 11.[144][145] The S-IVB third stage which performed Apollo 11’s trans-lunar injection remains in a solar orbit near to that of Earth.[146]

Moon rocks

The main repository for the Apollo Moon rocks is the Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. For safekeeping, there is also a smaller collection stored at White Sands Test Facility near Las Cruces, New Mexico. Most of the rocks are stored in nitrogen to keep them free of moisture. They are handled only indirectly, using special tools. Over 100 research laboratories around the world conduct studies of the samples, and approximately 500 samples are prepared and sent to investigators every year.[147][148]

In November 1969, Nixon asked NASA to make up about 250 presentation Apollo 11 lunar sample displays for 135 nations, the fifty states of the United States and its possessions, and the United Nations. Each display included Moon dust from Apollo 11. The rice-sized particles were four small pieces of Moon soil weighing about 50 mg and were enveloped in a clear acrylic button about as big as a United States half dollar coin. This acrylic button magnified the grains of lunar dust. The Apollo 11 lunar sample displays were given out as goodwill gifts by Nixon in 1970.[149]

Notas

- ↑ 1.01,11,21,31.4 Sarah Loff, Apollo 11 Mission Overview NASA, May 15, 2019. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ↑ 2.02.12.22.32.4 Apollo 11 (AS-506) Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ↑ David R. Williams, Apollo Landing Site CoordinatesNASA. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- ↑ 4.004.014.024.034.044.054.064.074.084.094.104.11 Richard W. Orloff, Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference NASA History Series SP-4029 (Washington, DC: NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans, 2000, ISBN 978-0160506314).

- ↑ 5.05.1 Eric Jones, One Small Step, Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal, April 8, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ↑ John M. Logsdon, The Decision to Go to the Moon: Project Apollo and the National Interest (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1976, ISBN 978-0226491752, 134.

- ↑ Logsdon 1976, 13–15.

- ↑ Courtney G. Brooks, James M. Grimwood, and Loyd S. Swenson, Jr. Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft SP-4205, NASA History Series (Washington, DC: Scientific and Technical Information Branch, NASA, 1979, ISBN 978-0486467566), 1.

- ↑ Loyd S. Swenson, Jr., James M. Grimwood, and Charles C. Alexander, This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury The NASA History Series SP-4201, (Washington, DC: NASA, 1966), 101–106.

- ↑ Swenson, Grimwood, and Alexander, 134.

- ↑ Logsdon 1976, 121.

- ↑ Logsdon 1976, 112–117.

- ↑ President John F. Kennedy, Excerpt from the ‘Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs’ Delivered in person before a joint session of Congress May 25, 1961. NASA, May 24, 2004. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ↑ Eugene Keilen, ‘Visiting Professor’ Kennedy Pushes Space Age Spending The Rice Thresher, September 19, 1962. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ↑ John F. Kennedy Moon Speech—Rice Stadium, September 12, 1962. NASA. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ↑ Charles Fishman, What You Didn’t Know About the Apollo 11 Mission. Smithsonian Magazine, June 2019. Retrieved February 18, 2020.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 15.

- ↑ John M. Logsdon, John F. Kennedy and the Race to the Moon (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, ISBN 978-0230110106), 32.

- ↑ Address at 18th U.N. General Assembly John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, September 20, 1963. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ↑ The Rendezvous That Was Almost Missed, NASA Langley Research Center Office of Public Affairs, December 1992. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 72–77.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 48–49.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 181–182, 205–208.

- ↑ Interplanetary Monitoring Platform: Engineering History and Achievements NASA, August 29, 1989, 1, 11, 134. Retrieved February 20 2020.

- ↑ Paul Ceruzzi, Apollo Guidance Computer and the First Silicon Chips Smithsonian Institution, October 14, 2015. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 214–218.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 265–272.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 274–284.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 292–300.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 303–312.

- ↑ Marcus Lindros, The Soviet Manned Lunar Program Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Jonathan Brown, Recording tracks Russia’s Moon gatecrash attempt The Independent, July 3, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 374.

- ↑ James R. Hansen, First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong (New York, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005, ISBN 978-0743256315), 312–313.

- ↑ Michael Collins, Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut’s Journeys (1974; New York: Cooper Square Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0815410287), 288–289.

- ↑ Walter Cunningham, The All-American Boys (ipicturebooks, 2010, ISBN 978-1876963248), 109.

- ↑ Hansen, 338–339.

- ↑ Collins, 2001, 434–435.

- ↑ Hansen, 359.

- ↑ Hansen, 359.

- ↑ 41.041.141.2 Mark Garcia, 50 Years Ago: Lunar Landing Sites Selected NASA, February 8, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ 42.042.1 Edgar M. Cortright, Scouting the Moon Apollo Expeditions to the Moon, (Washington, DC: NASA SP:350), 1975, 79–102. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ↑ David Harland, Exploring the Moon: The Apollo Expeditions (London; New York: Springer, 1999, ISBN 978-1852330996), 19.

- ↑ Michael Collins, Flying to the Moon: An Astronauts Story (New York: Square Fish, 1994 (original 1976) ISBN 978-0374423568), 7.

- ↑ J.O. Cappellari, Jr., Apollo 10 Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Andrew Chaikin, A Man on the Moon: The Triumphant Story Of The Apollo Space Program (New York, NY: Penguin Group, 1994, ISBN 978-0140272017), 148.

- ↑ Chaikin, 148.

- ↑ Collins, 2001, 347.

- ↑ Buzz Aldrin and Ken Abraham, No Dream is Too High: Life Lessons from a Man who Walked on the Moon (Washington, DC :National Geographic, 2016, ISBN 978-1426216497), 57–58.

- ↑ Hansen, 363–365.

- ↑ Chaikin, 149.

- ↑ Chaikin, 150.

- ↑ James Schefter, The Race: The Uncensored Story of How America Beat Russia to the Moon (New York: Doubleday, 1999, ISBN 978-0385492539), 281.

- ↑ Hansen, 371–372.

- ↑ Charles D. Benson and William B. Faherty, Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations, (Washington, DC: NASA, 1978, ISBN 978-1470052676), 472.

- ↑ 56.056.156.256.356.4 Benson and Faherty, 474-475.

- ↑ Benson and Faherty, 355–356.

- ↑ Collins, 2001, 355–357.

- ↑ David Woods, Kenneth D. McTaggart, and Frank O’Brien, Day 1, Part 1: Launch Apollo Flight Journal, January 8, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Brooks, Grimwood, and Swenson, 338.

- ↑ President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary Richard Nixon Presidential Library, July 16, 1969. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Marshall Space Flight Center, Technical Information Summary, Apollo-11 (AS-506) Apollo Saturn V Space Vehicle, Document ID: 19700011707; Accession Number: 70N21012; Report Number: NASA-TM-X-62812; S&E-ASTR-S-101-69, Huntsville, AL: NASA, June 1969. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ↑ W. David Woods, Kenneth D. MacTaggart, and Frank O’Brien, Day 4, part 1: Entering Lunar Orbit Apollo Flight Journal, February 10, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Apollo 11 Lunar Landing Mission Press Kit NASA, July 6, 1969. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ 65.0065.0165.0265.0365.0465.0565.0665.0765.0865.0965.10 Mission Evaluation Team, Apollo 11 Mission Report NASA, 1971. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ↑ Edgar M. Cortright (ed.), The Eagle Has landed Apollo Expeditions to the Moon SP-350, Washington, DC: NASA, 1975. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ↑ David A. Mindell, Digital Apollo: Human and Machine in Spaceflight (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0262134972), 220–221

- ↑ Margaret H. Hamilton and William R. Hackler, “Universal Systems Language: Lessons Learned from Apollo” Computer 41 (12) December 2008, 34–43.

- ↑ Margaret H. Hamilton, “Computer Got Loaded”, Datamation, March 1, 1971, 13.

- ↑ Chaikin, 196.

- ↑ Mindell, 195–197.

- ↑ Chaikin, 197.

- ↑ Chaikin, 198–199.

- ↑ Chaikin, 199.

- ↑ Mindell, 226.

- ↑ Paul Fjeld, The Biggest Myth about the First Moon Landing Horizons 38(6), June 2013, 5–6. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ James Donovan, Shoot for the Moon: The Space Race and the Extraordinary Voyage of Apollo 11 (Little, Brown and Company, 2019, ISBN 978-0316341783).

- ↑ Eric Jones, Post-landing Activities Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal, NASA, 1995. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Chaikin, 204, 623.

- ↑ Cortright, 215.

- ↑ Eric M. Jones and Ken Glover, Primeros pasos Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal, NASA, 1995. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Ricahrd S. Johnston, Lawrence F. Dietlin and Charles A. Berry (eds.), Biomedical Results of Apollo (Washington, DC: NASA, 1975), 115–120. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ Richard Macey, One giant blunder for mankind: how NASA lost Moon pictures The Sydney Morning Herald, August 5, 2006. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ 84.084.1 John M. Sarkissian, On Eagle’s Wings: The Parkes Observatory’s Support of the Apollo 11 Mission Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia 18(3), 2001. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ↑ William Gardner, Before the Fall: An Inside View of the Pre-Watergate White House (London; New York: Routledge Press, 2017, 978-1351314589), 143.

- ↑ Jacob Stern, One Small Controversy About Neil Armstrong’s Giant Leap—When, exactly, did the astronaut set foot on the moon? No one knows El Atlántico, July 23, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Shelley Canright, Apollo Moon Landing—35th Anniversary NASA, July 15, 2004. Retrieved February 20, 2020. Includes the “a” article as intended.

- ↑ Armstrong ‘got Moon quote right’ BBC News’, October 2, 2006. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Pallab Ghosh, Armstrong’s ‘poetic’ slip on Moon BBC News, June 3, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Charles Meyer, Contingency Soil Lunar Sample Compendium , NASA, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ 91.091.1 “A Flag on the Moon” The Attic. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Apollo 11 and Nixon, https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/american_originals/apollo11.html “The President held an interplanetary conversation with Apollo 11 Astronauts, Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin on the Moon” National Archives and Records Administration, March 1996. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Frank Borman and Robert J. Serling, Countdown: An Autobiography (New York: Silver Arrow, 1988, ISBN 978-0688079291, 237–238.

- ↑ “Richard Nixon: Telephone Conversation With the Apollo 11 Astronauts on the Moon” The American Presidency Project, July 20, 1969. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ↑ Harland, 28–29.

- ↑ University of Western Australia, Moon-walk mineral discovered in Western Australia Science Daily, January 17, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Eric M. Jones, EASEP Deployment and Closeout Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal, NASA, 1995. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “Neil Armstrong Explains His Famous Apollo 11 Moonwalk” Space.com, December 10, 2010. February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Eric M. Jones, “Trying to Rest”, Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal, NASA, 1995. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ White House ‘Lost In Space’ Scenarios The Smoking Gun. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Jim Mann, “The Story of a Tragedy That Was Not to Be” Los Angeles Times, July 7, 1999. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ William Safire, “Essay; Disaster Never Came” Los New York Times, July 12, 1999. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “The untold story: how one small silicon disc delivered a giant message to the Moon” November 15, 2007. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “Apollo 11 Goodwill Messages” NASA, July 13, 1969. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ 105.0105.1105.2105.3 Michael Collins and Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr. “The Eagle Has landed”, Apollo Expeditions to the Moon SP-350, Cortright, Edgar M. (ed.). Washington, DC: NASA, 1975, 203–224. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ↑ “American flags still standing on the Moon, say scientists”, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/science/space/9439047/, The Daily Telegraph, June 30, 2012, Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ David R. Williams, “Apollo Tables” NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Psalms 8:3–4 KJV Retrieved February 22, 2020

- ↑ Rachel Rodriguez, “The 10-year-old who helped Apollo 11, 40 years later” CNN, July 20, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “SMG Weather History—Apollo Program”, NOAA. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Jeremy Deaton, ‘They would get killed’: The weather forecast that saved Apollo 11 El Washington Post, July 18, 2019. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ↑ Scott W. Carmichael, Moon Men Return: USS Hornet and the Recovery of the Apollo 11 Astronauts (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1591141105), 184–185.

- ↑ Carmichael, 186–188.

- ↑ Carmichael, 199–200.

- ↑ Johnston, Dietlein and Berry, 406–424.

- ↑ Remarks to Apollo 11 Astronauts Aboard the U.S.S. Hornet Following Completion of Their Lunar Mission The American Presidency Project, July 24, 1969. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ↑ Extra-Terrestrial Exposure, 34 Fed. Reg. 11975, July 16, 1969, codified at 14 C.F.R. pt. 1200. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ↑ “A Front Row Seat For History” NASA, July 15, 2004. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Carmichael, 118.

- ↑ Ivan D. Ertel, Roland W. Newkirk, and Courtney G. Brooks, Man Circles the Moon, the Eagle Lands, and Manned Lunar Exploration The Apollo Spacecraft—A Chronology SP-4009, Vol. IV. Part 3 (1969 3rd quarter), Washington, DC: NASA, 1978. Retrieved February 23, 2020.

- ↑ Richard M. Nixon, “Remarks at a Dinner in Los Angeles Honoring the Apollo 11 Astronauts” The American Presidency Project, August 13, 1969. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Merriman Smith, “Astronauts Awed by the Acclaim” The Honolulu Advertiser, August 14, 1969, 1. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ↑ “The Apollo 11 Crew Members Appear Before a Joint Meeting of Congress” United States House of Representatives, September 19, 1969. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “Jean P. Haydon Museum” Fodor’s Travel. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “Apollo 11 Crew Starts World Tour” Associated Press, September 29, 1969, 1. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ↑ “Japan’s Sato Gives Medals to Apollo Crew” Los Angeles Times, November 5, 1969, 20. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ↑ “Australia Welcomes Apollo 11 Heroes” The Sydney Morning Herald, November 1, 1969, 1. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ↑ “Lunar Missions: Apollo 11” Archived October 24, 2008. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ↑ Roger D. Lanius, “Project Apollo: A Retrospective Analysis”. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Andrew Chaikin, “Live from the Moon: The Societal Impact of Apollo, Societal Impact of Spaceflight, Steven J. Dick and Roger D. Launius, eds., NASA SP-4801, 2007, 57. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- ↑ Chaikin, 2007, 58.

- ↑ “Apollo 11” History, August 23, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Howard E. McCurdy, Space and the American Imagination (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997, ISBN 978-1560987642), 106–107.

- ↑ Chaikin, 1994, 631.

- ↑ John Noble Wilford, “Russians Finally Admit They Lost Race to Moon” New York Times, December 18, 1989. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ↑ Saswato R. Das, “The Moon Landing through Soviet Eyes: A Q&A with Sergei Khrushchev, son of former premier Nikita Khrushchev” Científico americano, July 16, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “Museum in DC” Smithsonian Air and Space Museum, May 3, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “Apollo 11 Command Module, ‘Columbia'” Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Rebecca Makse, “Apollo 11 Moonship To Go On Tour” Air and Space Magazine, February 22, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “Neil Armstrong’s sons help open exhibit of father’s spacecraft in Ohio” September 30, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “LRO Sees Apollo Landing Sites” NASA, July 17, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “Location of Apollo Lunar Modules” Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “Amazon boss Jeff Bezos ‘finds Apollo 11 Moon engines'” BBC News, March 28, 2012. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Emi Kolawole, “Bezos Expeditions retrieves and identifies Apollo 11 engine #5, NASA confirms identity” El Washington Post, July 19, 2013. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “Apollo 11 engine find confirmed” Albuquerque Journal, July 21, 2013, 5. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ↑ Apollo 11 SIVB NSSDCA/COSPAR ID: 1969-059B NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ “Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility” NASA. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Kristen Flavin, “The mystery of the missing Moon rocks” World, September 10, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ↑ Robert Pearlman, “Where today are the Apollo 11 goodwill lunar sample displays? collectSPACE. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

References

- Aldrin, Buzz, and Ken Abraham. No Dream is Too High: Life Lessons from a Man who Walked on the Moon. Washington, DC: National Geographic, 2016. ISBN 978-1426216497

- Bates, James R., W.W. Lauderdale, and Harold Kernaghan. “ALSEP Termination Report” RP-1036, Washington, DC: NASA, April 1979. Retrieved on February 28, 2020.

- Benson, Charles D., and William B. Faherty. Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations. Washington, DC: NASA, 1978, ISBN 978-1470052676

- Bilstein, Roger E. “Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicle”, SP=4206 NASA History Series, Washington, DC: NASA, 1980. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- Borman, Frank and Robert J. Serling. Countdown: An Autobiography. New York: Silver Arrow, 1988. ISBN 978-0688079291

- Brooks, Courtney G., James M. Grimwood, and Loyd S. Swenson, Jr. Chariots for Apollo: A History of Manned Lunar Spacecraft. SP-4205, NASA History Series, Washington, DC: Scientific and Technical Information Branch, NASA, 1979. ISBN 978-0486467566

- Cappellari, J.O. Jr., “Where on the Moon? An Apollo Systems Engineering Problem.” Bell System Technical Journal 51(5) (June 1972): 955–1126.

- Carmichael, Scott W. Moon Men Return: USS Hornet and the Recovery of the Apollo 11 Astronauts. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1591141105