Movimento afro-americano pelos direitos civis (1955-1968)

[ad_1]

a Movimento Americano pelos Direitos Civis (1955-1968) foi um movimento bíblico que teve importantes consequências sociais e políticas para os Estados Unidos. Clérigos negros como o reverendo Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy, Joseph Lowery, Wyatt T. Walker, Fred Shuttlesworth e muitos outros confiaram na fé religiosa estrategicamente aplicada para resolver os teimosos problemas raciais da América. Os líderes cristãos negros e seus aliados brancos se uniram para desafiar o sistema imoral de segregação racial. O movimento procurou abordar e retificar as injustiças do racismo das gerações anteriores, empregando o método de resistência não violenta que eles acreditavam ter sido inspirado pela vida e sacrifício de Jesus Cristo.

Os fundadores dos Estados Unidos escreveram sobre os direitos inalienáveis da humanidade à vida, à liberdade e à busca da felicidade, mas muitos não acreditavam que isso devesse se aplicar a escravos negros ou mulheres. O Movimento dos Direitos Civis dos Estados Unidos travou uma década de luta muito depois do fim da escravidão e depois de outros marcos na luta para superar as práticas discriminatórias e segregacionistas. O racismo obstrui o desejo da América de ser uma terra de igualdade humana; a luta por direitos iguais também foi uma luta pela alma da nação.

Introdução

De seu nascimento em 1776 a 1955, o “American Experiment” – apesar de suas qualidades maravilhosas – ainda sofreu com a desigualdade racial e a injustiça. Essas realidades contradiziam a igualdade e a linguagem religiosa na raiz da fundação da nação. Finalmente, em 1955, o progresso em direção à igualdade racial deu um grande salto em comparação com o progresso lento e gradual visto antes dessa época. Os campeões do Movimento dos Direitos Civis sempre incluíram a linguagem religiosa em sua batalha por justiça e relações raciais saudáveis.

Com a derrota dos Estados Confederados da América no final da Guerra Civil, a nação entrou em um período de 12 anos (1865-1877) conhecido como Reconstrução. Mas de 1877 até a virada do século, uma trágica proliferação de leis racialmente discriminatórias e violência contra os negros americanos emergiu. Os estudiosos geralmente concordam que este período é o ponto mais baixo nas relações raciais americanas.

Embora o Congresso tenha adotado a Décima Quarta Emenda para garantir proteção igual para os negros, nos estados do Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Geórgia (estado), Flórida, Carolina do Sul, Carolina do Norte, Virgínia, Arkansas, Tennessee, Oklahoma e Kansas, eleitos, nomeados e / ou contratados, surgiram funcionários do governo que começaram a exigir e / ou permitir discriminação flagrante por meio de vários mecanismos. Estes incluíam:

- segregação racial: confirmada pela decisão da Suprema Corte dos Estados Unidos em Plessy vs. Ferguson em 1896, que foi legalmente ordenado, regionalmente, pelos estados do sul, e nacionalmente no nível local de governo;

- a supressão ou privação de voto nos estados do sul;

- negação de oportunidades ou recursos econômicos em nível nacional; Y

- atos de violência terrorista pública e privada contra americanos negros, violência que muitas vezes era auxiliada e estimulada por autoridades governamentais.

Embora a discriminação racial estivesse presente em todo o país, foi especificamente em toda a região dos estados do sul onde a combinação de intolerância legalmente sancionada, atos públicos e privados de discriminação, oportunidades econômicas marginalizadas e terror dirigido aos negros congelou em um sistema que veio a ser identificado. como Jim Crow. Por causa de seu ataque direto e implacável ao sistema e pensamento de Jim Crow, alguns estudiosos referem-se ao Movimento dos Direitos Civis como a “Segunda Reconstrução”.

Antes do Movimento dos Direitos Civis de 1955-1968, as estratégias convencionais empregadas para abolir a discriminação contra os negros americanos incluíam litígios e esforços de lobby por organizações tradicionais, como a Associação Nacional para o Avanço de Pessoas de Cor (NAACP). Esses esforços foram a marca registrada do Movimento dos Direitos Civis Americanos de 1896 a 1954. No entanto, em 1955, devido à política de “Resistência em Massa” implantada por defensores intransigentes da segregação racial e supressão eleitoral, os cidadãos Partes privadas conscientes ficaram consternadas com as abordagens gradualistas para efetuar a dessegregação por decreto governamental. Em resposta, os devotos dos direitos civis adotaram uma estratégia dupla de ação direta combinada com resistência não violenta, empregando atos de desobediência civil. Tais atos serviram para incitar situações de crise entre defensores dos direitos civis e autoridades governamentais. Essas autoridades, nos níveis federal, estadual e local, geralmente tiveram que responder com ações imediatas para encerrar os cenários de crise. E os resultados foram vistos como cada vez mais favoráveis aos manifestantes e sua causa. Algumas das diferentes formas de desobediência civil empregadas incluem boicotes, praticados com sucesso pelo Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955-1956) no Alabama; “mudas”, como demonstrou a influente Greensboro (1960) plantada na Carolina do Norte; e marchas de protesto, conforme exibido pelas marchas Selma a Montgomery (1965) no Alabama.

As principais realizações do Movimento dos Direitos Civis são:

- vitória legal no Brown v. Conselho de Educação (1954) caso que anulou a doutrina jurídica de “separados, mas iguais” e tornou a segregação legalmente inadmissível

- Aprovação da Lei dos Direitos Civis de 1964, que proibia a discriminação nas práticas de emprego e em locais públicos

- aprovação da Lei de Direitos de Voto de 1965, que salvaguardava o sufrágio negro

- aprovação da Lei de Serviços de Imigração e Nacionalidade de 1965, que mudou drasticamente a política de imigração dos EUA.

- Passagem da Lei dos Direitos Civis de 1968 que proibia a discriminação na venda e / ou aluguel de casas

Aproximando-se do ponto de ebulição: contexto histórico e pensamento em evolução

Brown v. Conselho de Educação (1954)

Em 17 de maio de 1954, a Suprema Corte dos Estados Unidos emitiu sua decisão histórica sobre o caso chamado Brown v. Conselho de Educação de Topeka (Kansas), em que os demandantes denunciaram que a prática de educar crianças negras em escolas públicas totalmente separadas de suas contrapartes brancas era inconstitucional. Na decisão do tribunal, foi afirmado que “a segregação de crianças brancas e mestiças nas escolas públicas prejudica as crianças de cor. O impacto é maior quando é sancionada por lei, porque a política de separação de raças é geralmente interpretado como denotando a inferioridade do grupo negro “.

Em sua decisão 9-0, o Tribunal declarou que Plessy vs. Ferguson, que estabeleceu a prática de segregação “separada, mas igual”, era inconstitucional e ordenou que a segregação estabelecida fosse eliminada gradualmente ao longo do tempo.

O assassinato de Emmett Till (1955)

Assassinatos de negros americanos por brancos ainda eram bastante comuns na década de 1950 e ainda não eram punidos em todo o sul. No entanto, o assassinato de Emmett Till, um adolescente de Chicago que estava visitando parentes em Money, Mississippi, no verão de 1955, foi diferente. Durante as horas antes do amanhecer de 28 de agosto, o jovem foi brutalmente espancado por seus dois sequestradores brancos, que então atiraram em Till e jogaram seu corpo no rio Tallahatchie. A idade da criança; a natureza de seu crime (supostamente assobiar para uma mulher branca em um supermercado); e a decisão de sua mãe de manter o caixão aberto em seu funeral, mostrando assim a espancada horrivelmente selvagem que havia sido infligida a seu filho; tudo trabalhou para impulsionar em um causar celebração que de outra forma poderia ter sido relegada a uma estatística de rotina. Até 50.000 pessoas podem ter visto o corpo de Till na casa funerária de Chicago e muitos milhares mais foram expostos às evidências de seu assassinato maliciosamente injusto quando uma fotografia de seu cadáver mutilado foi publicada em Jet Magazine.

Seus dois assassinos foram presos um dia após o desaparecimento de Till. Ambos foram absolvidos um mês depois, depois que o júri de todos os homens brancos deliberou por 67 minutos e depois retornou seu veredicto de “inocente”. O assassinato e a subsequente absolvição galvanizaram a opinião pública no Norte da mesma forma que a longa campanha para libertar os “Scottsboro Boys” na década de 1930. Após serem absolvidos, os dois assassinos deixaram claro que eles declararam abertamente que eram realmente culpados. Eles permaneceram livres e sem punição em consequência do processo judicial conhecido como “dupla incriminação”.

Ação em massa substitui litígio

Então Brown v. Board of Education, A estratégia convencional de litígio no tribunal começou a mudar para a “ação direta”, principalmente boicotes de ônibus, manifestações, caminhadas pela liberdade e táticas semelhantes, todas as quais dependiam de mobilização em massa, resistência não violenta e desobediência. civil, de 1955 a 1965. Isso foi, em parte, o resultado inadvertido de tentativas das autoridades locais de proibir e perseguir as principais organizações de direitos civis em todo o Extremo Sul. Em 1956, o estado do Alabama tinha efetivamente banido as operações da NAACP dentro de seus limites, exigindo que a organização apresentasse uma lista de seus membros e, em seguida, banindo-a de todas as atividades quando não o fizesse. Embora a Suprema Corte dos Estados Unidos finalmente tenha derrubado a proibição, houve um período de alguns anos em meados da década de 1950 durante o qual a NAACP não conseguiu operar. Durante esse tempo, em junho de 1956, o Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth deu início ao Movimento dos Direitos Humanos Cristãos do Alabama (ACMHR) para servir como suplente.

Iglesias e outras entidades locais de base também intervieram para preencher o vazio. Eles trouxeram consigo um estilo muito mais enérgico e amplo do que a abordagem mais legalista de grupos como o NAACP.

Rosa Parks e o boicote aos ônibus de Montgomery (1955-1956)

Possivelmente, o passo mais importante à frente ocorreu em Montgomery, Alabama, onde os ativistas de longa data da NAACP Rosa Parks e Edgar Nixon persuadiram o Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. a liderar o boicote aos ônibus de Montgomery em 1955. -1956.

Você sabia

Em 1º de dezembro de 1955, a Sra. Rosa Parks (a “Mãe do Movimento pelos Direitos Civis”), enquanto dirigia um ônibus público, recusou-se a ceder seu assento a um passageiro branco, depois que o motorista do ônibus lhe falou sobre isso. a fim de fazer isso. Posteriormente, a Sra. Parks foi presa, julgada e condenada por conduta desordeira e por violar uma lei local. Depois que a notícia desse incidente chegou a Montgomery, a comunidade negra do Alabama, cinquenta de seus líderes mais proeminentes se reuniram para discutir, criar estratégias e desenvolver uma resposta apropriada. Eles finalmente organizaram e lançaram o Boicote aos Ônibus de Montgomery, para protestar contra a prática de segregar negros e brancos no transporte público. O boicote bem-sucedido durou 382 dias (1956 foi um ano bissexto), até que o decreto local que legalizou a segregação de negros e brancos nos ônibus públicos falhou.

Líderes religiosos negros e ativistas em outras comunidades, como Baton Rouge, Louisiana, usaram a metodologia do boicote há relativamente pouco tempo, embora esses esforços muitas vezes diminuíssem após alguns dias. Em Montgomery, por outro lado, a Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) nasceu para liderar o boicote, e a MIA conseguiu sustentar o esforço por mais de um ano, até que uma ordem do tribunal federal exigiu que a cidade dessegregasse seu público. ônibus. O triunfo em Montgomery impulsionou o Dr. King ao status de luminar nacionalmente conhecido e gerou boicotes de ônibus subsequentes, como o bem-sucedido boicote de Tallahassee, Flórida, em 1956-1957.

Como resultado desses e de outros avanços, os líderes da MIA, Dr. King e Rev. John Duffy, se uniram a outros líderes da igreja que lideraram esforços de boicote semelhantes (como o Rev. CK Steele de Tallahassee e Rev. TJ Jemison de Baton Rouge, e outros ativistas, como Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, Ella Baker, A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin e Stanley Levison) para formar a Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) em 1957. O SCLC, com sede em Atlanta, Geórgia, não tentou criar uma rede de capítulos como a NAACP fez, mas em vez disso ofereceu treinamento e outra assistência para esforços locais para lidar com a segregação arraigada, enquanto arrecadava fundos, principalmente de fontes do Norte, para apoiar essas campanhas. . Ele fez da filosofia da não-violência tanto seu princípio central quanto seu método principal de desafiar sistematicamente o racismo tolerado.

Em 1957, Septima Clarke, Bernice Robinson e Esau Jenkins, com a ajuda do Highlander Research and Education Center, iniciaram as primeiras Escolas de Cidadania nas Ilhas do Mar da Carolina do Sul. O objetivo era alfabetizar os negros, capacitando-os a passar nos testes de elegibilidade. Com enorme sucesso, o programa triplicou o número de eleitores negros elegíveis na Ilha de St. John. O programa foi posteriormente assumido pelo SCLC e foi duplicado em outro lugar.

Desegregating Little Rock (1957)

Seguindo a decisão da Suprema Corte em Brown v. Conselho de Educação, o conselho escolar de Little Rock, Arkansas votou em 1957 para integrar o sistema escolar. A NAACP escolheu pressionar pela integração em Little Rock, em vez de Deep South, porque Arkansas era considerado um estado sulista relativamente progressista. No entanto, uma crise eclodiu quando o governador do Arkansas, Orval Faubus, convocou a Guarda Nacional em 4 de setembro para impedir a matrícula na Little Rock Central High School de nove estudantes negros americanos que haviam entrado com uma ação judicial pelo direito de comparecer. para uma instalação “apenas para brancos”. . No primeiro dia do ano letivo, apenas um dos nove alunos compareceu, pois não recebeu o telefonema avisando do perigo de ir à escola. Os brancos no terreno da escola a assediaram e a polícia teve que levá-la para um local seguro em um carro patrulha. Depois disso, os nove estudantes negros tiveram que viajar para o campus e ser escoltados por militares em jipes.

O próprio Faubus não era um segregacionista ferrenho, mas após sua indicação no ano anterior de que iria investigar para que Arkansas cumprisse o Castanho decisão, foram significativamente pressionados a rescindir essa promessa pela ala mais conservadora do Partido Democrático de Arkansas, que controlava a política naquele estado na época. Sob pressão, Faubus se opôs à integração e à ordem do tribunal federal que exigia isso.

A demissão de Faubus o colocou em rota de colisão com o presidente Dwight D. Eisenhower, que estava determinado a cumprir ordens de tribunais federais, apesar de sua própria ambivalência e indiferença na questão da dessegregação das escolas. . Eisenhower federalizou a Guarda Nacional e ordenou que retornassem ao quartel. O presidente então enviou elementos da 101ª Divisão Aerotransportada para Little Rock para proteger os alunos.

Todos os nove alunos puderam assistir às aulas, embora tivessem que passar por uma luva de brancos cuspidores e insultantes para ocuparem seus lugares no primeiro dia e tiveram que suportar o bullying de seus colegas durante todo o ano.

Caminhadas sentadas e liberdade

Sit-ins

O Movimento pelos Direitos Civis recebeu uma infusão de energia quando os alunos em Greensboro, Carolina do Norte; Nashville, Tennessee; e Atlanta, Geórgia, começou a “sentar-se” nas lanchonetes de algumas de suas lojas locais, protestando contra a recusa desses estabelecimentos de dessegregar. Esses manifestantes foram encorajados a se vestir profissionalmente, sentar-se em silêncio e ocupar qualquer outro banco para que potenciais apoiadores brancos pudessem se juntar a eles. Muitas dessas manifestações resultaram em autoridades locais usando força bruta para escoltar fisicamente os manifestantes para fora do refeitório. .

A técnica “sit-in” não era nova (o Congresso pela Igualdade Racial a usou para protestar contra a segregação no Meio-Oeste na década de 1940), mas chamou a atenção nacional para o movimento em 1960. O sucesso do movimento O protesto de Greensboro levou a uma série de campanhas estudantis em todo o sul. Provavelmente, o mais organizado, o mais disciplinado e o mais imediatamente eficaz foi o de Nashville, Tennessee. No final da década de 1960, as manifestações haviam se espalhado para todos os estados do sul e fronteiriços e até mesmo para Nevada, Illinois e Ohio. Os manifestantes se concentraram não apenas em lanchonetes, mas também em parques, praias, bibliotecas, teatros, museus e outros locais públicos. Ao serem presos, os manifestantes estudantis fizeram promessas de “prisão sem fiança” para chamar a atenção para sua causa e reverter o custo do protesto, sobrecarregando seus carcereiros com o fardo financeiro de espaço e alimentação na prisão.

Caminhadas pela liberdade

Em abril de 1960, os ativistas que lideraram essas manifestações formaram o Comitê de Coordenação Não-Violento do Estudante (SNCC) para promover essas táticas de confronto não-violento. Sua primeira campanha, em 1961, envolveu a realização de Freedom Tours, em que ativistas viajavam de ônibus pelo Deep South, para dessegregar os terminais das empresas de ônibus do sul, conforme exigido por lei. Federal. O líder do CORE, James Farmer, apoiou a ideia das caminhadas pela liberdade, mas, no último minuto, desistiu de participar.

As caminhadas pela liberdade provaram ser uma missão extremamente perigosa. Em Anniston, Alabama, um ônibus foi bombardeado e seus passageiros foram forçados a fugir para salvar suas vidas. Em Birmingham, onde um informante do FBI relatou que o Comissário de Segurança Pública Eugene “Bull” Connor havia encorajado a Ku Klux Klan a atacar um grupo de Freedom Riders “até que parecia que um bulldog os havia pego”, o os pilotos foram severamente espancados. No silêncio assustador de Montgomery, Alabama, uma multidão atacou outro ônibus cheio de passageiros, deixando John Lewis inconsciente com uma caixa e quebrando Revista vida fotógrafo Don Urbrock no rosto com sua própria câmera. Uma dúzia de homens cercou Jim Zwerg, um estudante branco da Universidade Fisk, e o atingiu no rosto com uma mala, deixando seus dentes.

Os Freedom Riders não se saíram muito melhor na prisão, onde foram amontoados em celas minúsculas e sujas e esporadicamente espancados. Em Jackson, Mississippi, alguns prisioneiros foram forçados a trabalhos forçados em temperaturas de 100 graus. Outros foram levados para a Penitenciária Estadual do Mississippi em Parchman, onde sua comida foi deliberadamente retirada em excesso e seus colchões removidos. Às vezes, os homens eram suspensos nas paredes por “quebradores de bonecas”. As janelas das celas normalmente ficavam bem fechadas em dias quentes, dificultando a respiração.

O movimento estudantil envolveu figuras famosas como John Lewis, o ativista determinado que “continuou” apesar de muitos espancamentos e perseguições; James Lawson, o reverenciado “guru” da teoria e tática não violenta; Diane Nash, uma articulada e destemida defensora pública da justiça; Robert Parris Moses, pioneiro do registro eleitoral no Mississippi, a parte mais rural e perigosa do Sul; e James Bevel, um pregador apaixonado e organizador e facilitador carismático. Outros ativistas estudantis proeminentes foram Charles McDew; Bernard Lafayette; Charles Jones; Lonnie King; Julian Bond (associado à University of Atlanta); Hosea Williams (associado à Brown Chapel); e Stokely Carmichael, que mais tarde mudou seu nome para Kwame Ture.

Organizando-se no Mississippi

Em 1962, Robert Moses, representante do SNCC no Mississippi, reuniu organizações de direitos civis naquele estado – SNCC, NAACP e CORE – para formar o COFO, o Conselho de Organizações Federadas. O Mississippi era o mais perigoso de todos os estados do sul, mas Moses, Medgar Evers da NAACP e outros ativistas locais embarcaram em projetos de educação eleitoral de porta em porta em áreas rurais, determinados a recrutar estudantes para sua causa. Evers foi assassinado no ano seguinte.

Enquanto o COFO trabalhava no nível de base no Mississippi, Clyde Kennard tentou entrar na University of Southern Mississippi. Ele foi considerado um agitador racial pela Comissão de Soberania do Estado do Mississippi, foi considerado culpado de um crime que não cometeu e foi condenado a sete anos de prisão. Ele fez três anos e mais tarde foi solto, mas apenas porque tinha câncer intestinal e o governo do Mississippi não queria que ele morresse na prisão.

Dois anos depois, James Meredith entrou com um processo de admissão na Universidade do Mississippi em setembro de 1962, e então tentou entrar no campus em 20 de setembro, 25 de setembro e novamente em 26 de setembro, apenas para ser bloqueado por Governador do Mississippi Ross R. Barnett. Barnett proclamou: “Nenhuma escola será integrada no Mississippi enquanto eu for seu governador.” Depois que o Tribunal de Apelações do Quinto Circuito manteve Barnett e o governador Paul B. Johnson Jr. por desacato, com multas de mais de US $ 10.000 para cada dia, eles se recusaram a permitir que Meredith se inscrevesse. Meredith, escoltada por um bando de marechais dos EUA, entrou no campus em 30 de setembro de 1962.

Estudantes brancos e não estudantes começaram a protestar naquela noite, primeiro jogando pedras nos oficiais dos EUA que guardavam Meredith no Lyceum Hall e depois atirando neles. Duas pessoas foram mortas, incluindo um jornalista francês; 28 oficiais de justiça sofreram ferimentos a bala e outros 160 ficaram feridos. Depois que a Patrulha Rodoviária do Mississippi retirou-se do campus, o presidente Kennedy enviou o exército regular ao campus para reprimir o levante. Meredith pôde começar as aulas no dia seguinte, depois que as tropas chegaram.

O Movimento Albany (1961-1967)

Em novembro de 1961, a Conferência de Liderança Cristã do Sul (SCLC), que havia sido criticada por alguns ativistas estudantis por não participar mais plenamente das caminhadas pela liberdade, comprometeu muito de seu prestígio e recursos para uma campanha de dessegregação. em Albany, Geórgia. O Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., que havia sido duramente criticado por alguns ativistas do SNCC por sua distância dos perigos enfrentados pelos organizadores locais, e que foi posteriormente apelidado pelo apelido zombeteiro de “De Lawd”, interveio pessoalmente a ajudar a campanha dirigida tanto pelos organizadores do SNCC quanto pelos líderes locais.

A campanha foi um fracasso, devido às táticas astutas do chefe de polícia local, Laurie Pritchett. Conteve o movimento com sucesso sem provocar o tipo de ataque violento aos manifestantes que inflamou a opinião nacional e gerou protestos na comunidade negra. Pritchett também contatou todas as prisões e cadeias em um raio de 60 milhas de Albany e providenciou para que os manifestantes presos fossem trazidos para uma dessas instalações, permitindo-lhes espaço suficiente para ficar em suas próprias prisões. Além desses arranjos, Pritchett também viu a presença de King como uma ameaça e forçou a libertação do líder para impedi-lo de reunir a comunidade negra. King partiu em 1962 sem obter vitórias dramáticas. O movimento local, no entanto, continuou a lutar e fez avanços significativos nos anos seguintes.

A campanha de Birmingham (1963-1964)

O movimento Albany finalmente provou ter sido uma educação importante para o SCLC quando a organização lançou sua Campanha de Birmingham em 1963. Este esforço se concentrou em um objetivo de curto prazo, a dessegregação das empresas comerciais do centro de Birmingham, em vez de desagregação total, como em Albany. Ele também foi ajudado pela resposta brutalmente bárbara das autoridades locais, particularmente a de Eugene “Bull” Connor, o Comissário de Segurança Pública. Connor havia perdido uma recente eleição para prefeito para um candidato segregacionista menos fanático, mas se recusou a aceitar a autoridade do novo prefeito.

A campanha pelos direitos de voto empregou uma variedade de táticas de confronto não violentas, incluindo protestos, ajoelhar-se em igrejas locais e uma marcha até o prédio do condado para indicar o início de uma campanha de recenseamento eleitoral. A cidade, no entanto, obteve uma ordem judicial que excluiu todos os protestos. Convencida de que a ordem era inconstitucional, a campanha a contestou e se preparou para prisões em massa de seus apoiadores. O Dr. King escolheu estar entre os presos em 12 de abril de 1963.

Enquanto estava na prisão em 16 de abril, King escreveu sua famosa “Carta da Cadeia de Birmingham” nas margens de um jornal, já que as autoridades da prisão não lhe concederam nenhum papel para escrever durante seu isolamento. Apoiadores, enquanto isso, pressionaram o governo Kennedy a intervir e garantir a libertação de King, ou pelo menos melhorar as condições. King finalmente teve permissão para ligar para sua esposa, que estava se recuperando em casa após o nascimento do quarto filho, e finalmente foi solto em 19 de abril.

A campanha, no entanto, estava vacilando neste ponto, já que o movimento estava ficando sem manifestantes dispostos a correr o risco de prisão. Os organizadores do SCLC propuseram uma alternativa ousada e altamente polêmica: convocar alunos do ensino médio a participarem da atividade de protesto. Quando mais de 1.000 alunos deixaram a escola em 2 de maio para se juntar às manifestações no que seria chamado de Cruzada das Crianças, mais de 600 acabaram na prisão. Isso foi interessante, mas durante o encontro inicial a polícia agiu com moderação. No dia seguinte, porém, mil outros estudantes se reuniram na igreja e Bull Connor lançou ferozes cães policiais sobre eles. Ele então girou impiedosamente as mangueiras de incêndio da cidade, que foram colocadas em um nível que arrancaria a casca de uma árvore ou separaria os tijolos da argamassa, diretamente em cima dos alunos. Câmeras de televisão transmitem para o país cenas de trombas d’água derrubando crianças em idade escolar indefesas e cães atacando manifestantes desarmados.

A indignação pública generalizada resultante levou o governo Kennedy a intervir com mais força nas negociações entre a comunidade empresarial branca e o SCLC. Em 10 de maio de 1963, as partes declararam um acordo para cancelar a segregação dos lanchonetes e outras acomodações públicas do centro, criar um comitê para eliminar práticas discriminatórias de contratação, organizar a libertação de manifestantes presos e estabelecer a mídia regular comunicação entre negros. e líderes brancos.

Nem todos na comunidade negra aprovaram o acordo. Fred Shuttlesworth foi particularmente crítico, pois acumulou grande ceticismo sobre a boa fé da estrutura de poder de Birmingham por causa de sua experiência em lidar com eles. A reação de certas partes da comunidade branca foi ainda mais violenta. O Gaston Motel, que abrigava a sede não oficial do SCLC, foi bombardeado, assim como a casa do Dr. [Martin Luther King, Jr.|King]]irmão, Reverendo A.D. Rei. Kennedy se preparou para federalizar a Guarda Nacional do Alabama, mas não concordou. Quatro meses depois, em 15 de setembro, membros da Ku Klux Klan bombardearam a Igreja Batista da Rua Dezesseis em Birmingham, matando quatro meninas.

O verão de 1963 também foi agitado. Em 11 de junho, o governador do Alabama, George Wallace, tentou bloquear a integração da Universidade do Alabama. El presidente John F. Kennedy envió suficiente fuerza para hacer que el gobernador Wallace se hiciera a un lado, permitiendo así la inscripción de dos estudiantes negros. Esa noche, Kennedy se dirigió a la nación por televisión y radio con un histórico discurso de derechos civiles.[1] Al día siguiente en Mississippi, Medgar Evers fue asesinado.[2] La semana siguiente, como prometió, el 19 de junio de 1963, Kennedy presentó su proyecto de ley de derechos civiles al Congreso.[3]

La marcha sobre Washington (1963)

En 1941, A. Philip Randolph había planeado una Marcha en Washington en apoyo de las demandas para la eliminación de la discriminación laboral en las industrias de defensa. Él canceló la marcha cuando la administración de Roosevelt cumplió con esa demanda emitiendo la Orden Ejecutiva 8802, prohibiendo la discriminación racial y creando una agencia para supervisar el cumplimiento de la orden.

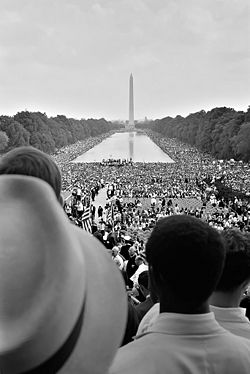

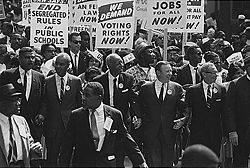

Randolph y Bayard Rustin fueron los principales planificadores de la segunda Marcha en Washington por el Empleo y la Libertad, que propusieron en 1962. La administración Kennedy presionó enérgicamente a Randolph y King para que la cancelaran, pero fue en vano. La marcha se realizó el 28 de agosto de 1963.

A diferencia de la marcha planificada de 1941, para la cual Randolph incluyó solo organizaciones lideradas por negros en la agenda, la Marcha de 1963 fue un esfuerzo de colaboración de todas las principales organizaciones de derechos civiles, el ala más progresista del movimiento obrero y otros grupos liberales. La Marcha tenía seis objetivos oficiales: “leyes significativas de derechos civiles; un programa de obras federales masivo; empleo pleno y justo; vivienda digna; el derecho al voto; y una educación integrada adecuada”. De estos, el enfoque central de la Marcha fue la aprobación del proyecto de ley de derechos civiles que la administración Kennedy había propuesto después de los disturbios en Birmingham.

La marcha fue un éxito asombroso, aunque no exento de controversias. Más de 200.000 manifestantes se reunieron frente al Lincoln Memorial, donde King pronunció su famoso discurso “Tengo un sueño”. Si bien muchos de los oradores de la manifestación aplaudieron a la Administración Kennedy por los esfuerzos (en gran medida ineficaces) que había realizado para obtener una legislación de derechos civiles nueva y más efectiva para proteger los derechos de voto y prohibir la segregación, John Lewis de SNCC criticó a la administración por lo poco que lo había hecho para proteger a los negros del sur y a los trabajadores de los derechos civiles que estaban siendo atacados en el sur profundo. Si bien atenuó sus comentarios bajo la presión de otros en el movimiento, sus palabras aún dolían:

Marchamos hoy por trabajos y libertad, pero no tenemos nada de qué estar orgullosos, porque cientos y miles de nuestros hermanos no están aquí, porque no tienen dinero para su transporte, porque están recibiendo salarios de hambre … o ningún salario. En conciencia, no podemos apoyar el proyecto de ley de derechos civiles de la administración.

Este proyecto de ley no protegerá a los niños pequeños y las ancianas de los perros policía y las mangueras de bomberos cuando participen en manifestaciones pacíficas. Este proyecto de ley no protegerá a los ciudadanos de Danville, Virginia, que deben vivir con miedo constante en un estado policial. Este proyecto de ley no protegerá a los cientos de personas que han sido arrestadas por cargos falsos como los de Americus, Georgia, donde cuatro jóvenes están en la cárcel, enfrentando la pena de muerte, por participar en protestas pacíficas.

Quiero saber: ¿de qué lado está el gobierno federal? La revolución es seria. Kennedy está tratando de sacar la revolución de las calles y llevarla a los tribunales. Escuche, señor Kennedy, las masas negras están en marcha por el empleo y la libertad, y debemos decirles a los políticos que no habrá un ‘período de reflexión’.

Después de la marcha, King y otros líderes de derechos civiles se reunieron con el presidente Kennedy en la Casa Blanca. While the Kennedy administration appeared to be sincerely committed to passing the bill, it was not clear that it had the votes to do so. But when President Kennedy was assassinated on November 22, 1963,[3] the new president, Lyndon Johnson, decided to assert his power in Congress to effect a great deal of Kennedy’s legislative agenda in 1964 and 1965, much to the public’s approval.

Mississippi Freedom Summer (1964)

In Mississippi during the summer of 1964 (sometimes referred to as the “Freedom Summer”), the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) used its resources to recruit more than one hundred college students, many from outside the state, to join with local activists in registering voters; teaching at “Freedom Schools”; and organizing the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. The work was still as dangerous as ever, and on June 21, three civil rights workers (James Chaney, a young black Mississippian and plasterer’s apprentice; Andrew Goodman, a Jewish anthropology student from Queens College, New York; and Michael Schwerner, a Jewish social worker from Manhattan’s Lower East Side) were all abducted and murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan, among whom were deputies of the Neshoba County Sheriff’s Department.

The disappearance of the three men sparked a national uproar. What followed was a Federal Bureau of Investigation inquiry, although President Johnson had to use indirect threats of political reprisals against J. Edgar Hoover, to force the indifferent bureau director to actually conduct the investigation. After bribing at least one the murderers for details regarding the crime, the FBI found the victims’ bodies on August 4, in an earthen dam on the outskirts of Philadelphia, Mississippi. Schwerner and Goodman had been shot once. Chaney, the lone black, had been savagely beaten and shot three times. During the course of that investigation, the FBI also discovered the bodies of a number of other Mississippi blacks whose disappearances had been reported over the past several years without arousing any interest or concern beyond their local communities.

The disappearance of these three activists remained on the public interest front burner for the entire month and-a-half until their bodies were found. President Johnson used both the outrage over their deaths and his redoubtable political skills to bring about the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which bars discrimination in public accommodations, employment, and education. This legislation also contains a section dealing with voting rights, but the Voting Rights Act of 1965 addressed that concern more substantially.

The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (1964)

In 1963, in order to demonstrate black Mississippians’ commitment to exercising their voting rights, COFO had held a “Freedom Vote Campaign.” More than 90,000 people voted in mock elections, which pitted candidates from the “Freedom Party” against the official state Democrat Party candidates. In 1964 organizers launched the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) to challenge the all-white slate from the state party. When Mississippi voting registrars refused to recognize their candidates, the organizers held their own primary, selecting Fannie Lou Hamer, Annie Devine, and Victoria Gray to run for United States Congress. Also chosen was a slate of delegates to represent Mississippi at the 1964 Democratic National Convention.

Their presence in Atlantic City, New Jersey, however, was very inconvenient for the convention’s hosts, who had planned a triumphal celebration of the Johnson Administration’s civil rights achievements, not a fight over racism within the Democratic Party itself. Johnson was additionally worried about the inroads that Barry Goldwater’s campaign was making upon what previously had been the Democratic stronghold of the “Solid South.” There was also concern over the support that George Wallace had received during the Democratic primaries in the North. Other all-white delegations from other Southern states had threatened to walk out if the all-white slate from Mississippi was not seated.

Johnson could not, however, prevent the MFDP from taking its case to the Credentials Committee, where Fannie Lou Hamer eloquently testified as to the beatings that she and others had received and the threats they repeatedly faced for trying to register as voters. Turning to the television cameras, Hamer asked, “Is this America?”

Johnson attempted to preempt coverage of Hamer’s testimony by hastily scheduling a speech of his own. When that failed to move the MFDP off the evening news, he offered the MFDP a “compromise,” under which it would receive two non-voting, at-large seats, while the white delegation sent by the official Democratic Party would retain its seats. The proposed compromise was angrily rejected. As stated by Aaron Henry, Medgar Evers’ successor as president of the NAACP’s Mississippi Chapter:

Now, Lyndon made the typical white man’s mistake: Not only did he say, ‘You’ve got two votes,’ which was too little, but he told us to whom the two votes would go. He’d give me one and Ed King one; that would satisfy. But, you see, he didn’t realize that sixty-four of us came up from Mississippi on a Greyhound bus, eating cheese and crackers and bologna all the way there. We didn’t have no money. Suffering the same way. We got to Atlantic City. We put up in a little hotel, three or four of us in a bed, four or five of us on the floor. You know, we suffered a common kind of experience, the whole thing. But now, what kind of fool am I, or what kind of fool would Ed have been, to accept gratuities for ourselves? You say, ‘Ed and Aaron can get in but the other sixty-two can’t.’ This is typical white man, picking black folks’ leaders, and that day is just gone.

Hamer put it even more succinctly:

We didn’t come all the way up here to compromise for no more than we’d gotten here. We didn’t come all this way for no two seats, ‘cause all of us is tired.

Even after it was denied official recognition, however, the MFDP kept up its agitation during the Atlantic City convention. When all but three of the “regular” Mississippi delegates left because they refused to pledge allegiance to the party, the MFDP delegates borrowed passes from sympathetic delegates and took the seats vacated by the Mississippi delegates, only to be subsequently removed by the national party. When they returned the next day to find that convention organizers had removed the previous day’s empty seats, the MFDP delegates stood huddled together and sang freedom songs.

Many within the MFDP and the Civil Rights Movement were disillusioned by the events at the 1964 convention, but that disenchantment did not destroy the MFDP itself. Instead, the party became more radical after Atlantic City, choosing to invite Malcolm X to speak at its founding convention and electing to oppose the Vietnam War.

For some of the movement’s devotees, a measure of comfort came at the end of the long, hard year of 1964 when, on December 10, in Oslo, Norway, Martin Luther King, Jr. was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, which he graciously accepted on behalf of all the committed, sacrificial adherents of non-violent resistance.[4]

Selma and the Voting Rights Act (1965)

By early 1965, SNCC had undertaken an ambitious voter registration campaign in Selma, Alabama, but had made little headway in the face of opposition from Selma’s top law enforcement official, Sheriff Jim Clark. After local residents entreated the SCLC for assistance, King traveled to Selma, intending to lead a number of marches. On Monday, February 1, he was arrested along with 250 other demonstrators. As the campaign ensued, marchers continued to meet violent resistance from police. On February 18, a state trooper mortally wounded Jimmie Lee Jackson, a 25-year-old pulpwood cutter. In his hospital bed, Jackson died two days later.

On Sunday, March 7, the SCLC’s Hosea Williams and the SNCC’s John Lewis led a march of 525 pilgrims, who intended to walk the 54 miles from Selma to the state capital in Montgomery. Only six blocks into the march, however, at the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Jefferson Davis Highway, Alabama state troopers and local law enforcement officers attacked the peaceful demonstrators with billy clubs, tear gas, rubber tubes wrapped in barbed wire, and bull whips. The defenseless marchers were driven back into Selma. John Lewis was knocked unconscious and dragged to safety, while at least 16 other marchers were hospitalized. Among those gassed and beaten was Amelia Boynton Robinson, who was at the center of civil rights activity at the time.

That night, the ABC Television film clip of the footage showing lawmen pummeling and brutalizing unresisting marchers provoked a national response similar to the one educed by the scenes from Birmingham two years earlier. Selma’s “Bloody Sunday” was exposed for the entire civilized world to see. Two days later, on March 9, led by King, the protestors performed a second, truncated march to the site of Sunday’s beatings and then turned and headed unharrassed back into town. But that night, a gang of local white toughs attacked a group of white Unitarian voting rights supporters, and fatally wounded the Rev. James Reeb. On March 11, in a Birmingham hospital, Reeb died. His murder triggered an earthquake of public white indignation, with outcries thundering forth from the American Jewish Committee, the AFL-CIO, and the United Steelworkers, to name a few. Then, on the evening of Sunday, March 15, President Johnson made a congressional appearance on television. His purpose was to convey to America the urgent necessity for a new and comprehensive voting-rights bill. Stated the president:

But even if we pass this bill, the battle will not be over. What happened in Selma is part of a far larger movement which reaches into every section and state of America. It is the effort of American Negroes to secure for themselves the full blessings of American life.[5]

Their cause must be our cause too. Because it is not just Negroes, but really it is all of us, who must overcome the crippling legacy of bigotry and injustice. And we shall overcome.[5]

On the heels of this sociopolitical sea change, Dr. King, for five days, led an en masse pilgrimage from Selma to Montgomery, to secure voting rights for Alabama blacks. What began on Sunday, March 21 as a trek by some 3,200 marchers, climaxed on Thursday, March 25, with some 25,000 people, safeguarded by eight hundred federal troops, proceeding nonviolently through Montgomery. Tragically, however, this march, as had so many others during this effort, ended in senseless violence. According to King biographer Stephen B. Oates:

That night, in a high-speed car chase, on Highway 80, Klansmen shot and killed civil-rights volunteer Viola Liuzzo; and the movement had another martyr and the nation another convulsion of moral indignation. Yet, as Ebony correspondent Simeon Booker put it, the great march really ended with two deaths that Thursday—Mrs. Liuzzo’s and Jim Crow’s.

Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 on August 6. The legislation suspended poll taxes, literacy tests, and other voter tests. It authorized federal supervision of voter registration in states and individual voting districts where such tests were being used. Blacks who had been barred from registering to vote finally had an alternative to the courts. If voting discrimination occurred, the 1965 Act authorized the attorney general of the United States to send federal examiners to replace local registrars. Johnson reportedly stated to some associates that his signing of the bill meant that the Democratic Party, for the foreseeable future, had forfeited the loyalty of the “Solid South.”

The Act, however, had an immediate and positive impact for blacks. Within months of its passage, 250,000 new black voters had been registered, one third of them by federal examiners. Within four years, voter registration in the South had more than doubled. In 1965, Mississippi had the highest black voter turnout—74 percent—and led the nation in the number of black public officials elected. In 1969, Tennessee had a 92.1 percent turnout; Arkansas, 77.9 percent; and Texas, 73.1 percent.

Several prominent white officials who had opposed the voting-rights campaign immediately paid the price. Selma’s Sheriff Jim Clark, notorious for using fire hoses and cattle prods to molest civil-rights marchers, was up for re-election in 1966. Removing the trademark “Never” pin from his uniform in an attempt to win the black vote, he ended up defeated by his challenger, as blacks gleefully voted just for the sake of removing him from office.

The fact of blacks winning the right to vote changed forever the political landscape of the South. When Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, fewer than one hundred blacks held elective office in the U.S. By 1989, there were more than 7,200. This included more than 4,800 in the South. Nearly every Black Belt county in Alabama had a black sheriff, and Southern blacks held top positions within city, county, and state governments. Atlanta had a black mayor, Andrew Young, as did Jackson, Mississippi—Harvey Johnson—and New Orleans, with Ernest Morial. Black politicians on the national level included Barbara Jordan, who represented Texas in Congress, and former mayor Young, who was appointed U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations during the Carter Administration. Julian Bond was elected to the Georgia Legislature in 1965, although political reaction to his public opposition to U.S. involvement in Vietnam prevented him from taking his seat until 1967. John Lewis currently represents Georgia’s 5th Congressional District in the United States House of Representatives, where he has served since 1987. Lewis sits on the House Ways and Means and Health committees.

Prison Reform

Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman (then known as Parchman Farm) is recognized for the infamous part it played in the United States Civil Rights Movement. In the spring of 1961, Freedom Riders (civil rights workers) came to the American South to test the authenticity of desegregation in public facilities. By the end of June, 163 Freedom Riders had been convicted in Jackson, Mississippi. Many were jailed in Parchman.

In 1970 the astute Civil Rights lawyer Roy Haber began taking statements from Parchman inmates, which eventually ran to fifty pages, detailing murders, rapes, beatings, and other abuses suffered by the inmates from 1969 to 1971 at Mississippi State Penitentiary. In a landmark case known as Gates v. Collier (1972), four inmates represented by Haber sued the superintendent of Parchman Farm for violation of their rights under the United States Constitution. Federal Judge William C. Keady found in favor of the inmates, writing that Parchman Farm violated the civil rights of the inmates by inflicting cruel and unusual punishment. He ordered an immediate end to all unconstitutional conditions and practices. Racial segregation of inmates was abolished, as was the “trustee system,” which had enabled certain inmates (i.e., “lifers”) to be armed with rifles and to have power and control over other prisoners.

The penitentiary was renovated in 1972, after the excoriating decision by Judge Keady, in which he wrote that the prison was an affront to “modern standards of decency.” In addition to the extirpation of the “trustee system,” the facility was made fit for human habitation.[6]

The American Jewish Community and the Civil Rights Movement

The evidence indicates that support for the Civil Rights Movement was quite strong throughout the American Jewish community. The Jewish philanthropist, Julius Rosenwald, funded dozens of primary schools, secondary schools, and colleges for blacks. He and other Jewish luminaries led their community in giving to some two thousand schools for black Americans. This list includes universities such as Howard, Dillard, and Fisk. At one time, some forty percent of Southern blacks were enrolled at these schools. Of the civil-rights lawyers who worked in the South, fifty percent were Jewish.

Reform Movement leaders such as Rabbi Jacob Rothchild were open in their support for the Movement’s goals. Noted scholar, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, professor of religion at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, marched with Dr. King in 1965 in Selma. Heschel also introduced King on the night of the latter’s address before the annual convention of the Rabbinical Assembly, convened in the Catskill Mountains on March 25, 1968. Stated Heschel:

Martin Luther King is a voice, a vision, and a way. I call upon every Jew to harken to his voice, to share his vision, to follow his way. The whole future of America will depend upon the impact and influence of Dr. King.[7]

Prior to King’s taking the podium that night, the rabbis had given him a special greeting—a rendition of “We Shall Overcome,” which they sang in Hebrew.

The PBS Television documentary, From Swastika to Jim Crow explores Jewish involvement with the civil rights movement, and demonstrates that Jewish professors (refugees from the Holocaust) came to teach at Southern black colleges in the 1930s and 1940s. Over time, there came to be heartfelt empathy and collaboration between blacks and Jews. Professor Ernst Borinski hosted dinners at which blacks, Jews and whites sat next to each other, a simple act that defied segregation. Black students sympathized with the cruelty these scholars had endured in Europe.[8]

The American Jewish Committee, American Jewish Congress, and Anti-Defamation League all actively promoted the cause of civil rights.

Unraveling alliances

King reached the height of popular lifetime acclaim, when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. One year later, his career had become embattled with frustrating challenges, as the liberal coalition that had made possible the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 began to fray. King was, by this time, becoming more estranged from the Johnson administration, breaking with it in 1965 by calling for both peace negotiations and a halt to the bombing of Vietnam. He moved further left during the ensuing years, shifting toward socialism and speaking of the need for economic justice and thoroughgoing changes in American society. He was now struggling to think beyond the conventional, established parameters of the civil-rights vision.

King’s efforts to broaden the scope of the Civil Rights Movement were halting and largely unsuccessful, however. He made several attempts, in 1965, to take the Movement into the North, to address issues of discrimination in employment and housing. His campaign in Chicago failed, as Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley marginalized the demonstrators by promising to “study” the city’s problems. The next year, in the notoriously racist Chicago suburb of Cicero, Illinois, white demonstrators, holding “White Power” signs, hurled stones at King and other marchers as they demonstrated against segregated housing.

Race riots (1963-1970)

Throughout the era of the Civil Rights Movement, several bills guaranteeing equality for black citizens were signed into law. Enforcement of these acts, however, particularly in Northern cities, was another issue altogether. After World War II, more than half of the country’s black population lived in Northern and Western cities, rather than in Southern rural areas. Migrating to these cities in search of better job opportunities and housing situations, blacks often did not find their anticipated lifestyles.

While from the sociopolitical standpoint urbanized blacks found themselves comparatively free from terrorism at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan, other equally or more pressing problems often loomed. From the socioeconomic standpoint, urban black neighborhoods were, in fact, among the poorest and most blighted in nearly every major city. Often rampant with unemployment and crime, and seemingly bereft of commercial development, these localities were accurately dubbed “ghettos.” Blacks customarily owned few, if any, of the neighborhood enterprises, and often worked menial or blue-collar jobs at a fraction of the wages that their white counterparts were paid. Often earning only enough money to afford the most dilapidated and/or most undesirable housing, many of these inner-city dwellers regularly found themselves applying for welfare. The paucity of wealth and its benefits took its toll on those struggling in abject poverty. Fueled by economic despair and its concomitant lack of self-esteem, vast numbers of black ghetto-dwellers were slavishly abusing cocaine, heroin, and other illegal drugs, long before large-scale numbers of whites ever began experimenting with them. In addition, the plethora of liquor stores abounding in these poor neighborhoods served only to make matters worse.

On the educational front, blacks attended schools that were typically their cities’ structurally and academically worst. And, inarguably, black neighborhoods were subject to criminality levels and concerns that white neighborhoods were not even remotely as plagued by. Throughout mainstream America, white law enforcement practitioners were trained to adhere to the motto, “To Protect and Serve.” In the case of black neighborhoods, however, it was often a different reality. Many blacks perceived that the police existed strictly to implement the slogan, “To Patrol and Control.” The fact of the largely white racial makeup of the police departments was a major factor with regard to this. Up until 1970, no urban police department in America was greater than 10 percent black, and in most black neighborhoods, blacks accounted for less than 5 percent of the police patrolmen. Not uncommon were arrests of people simply due to their being black. Years of such harassment, combined with the repletion of other detriments of ghetto life, finally erupted in the form of chaotic and deadly riots.

One of the first major outbreaks took place in Harlem, New York, in the summer of 1964. A 15-year-old black named James Powell was shot by a white Irish-American police officer named Thomas Gilligan, who alleged that Powell had charged him while brandishing a knife. In fact, Powell was unarmed. A mob of angry blacks subsequently approached the precinct station house and demanded Gilligan’s suspension. The demand was refused. Members of the mob then proceeded to ransack many local stores. Even though this precinct had promoted the New York Police Department’s first black station commander, neighborhood dwellers were so enraged and frustrated at the obvious inequalities and oppressions that they looted and burned anything in the locality that was not black-owned. This riot eventually spread to Bedford-Stuyvesant, the main black neighborhood in Brooklyn. Later, during that same summer, and for similar reasons, riots also broke out in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The following year, on August 6, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But in numerous neighborhoods, socioeconomic realities for blacks had not improved. One year later, in August 1966, in the South Central Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts, another riot broke out. Watts, like Harlem, was characterized by impoverished living conditions. Unemployment and drug abuse were rampant, and a largely white police department patrolled the neighborhood. While arresting a young man for drunk driving, the police, with onlookers gathered around, got into an argument with the suspect’s mother. This escalated, and a riot erupted, unleashing six days of sheer mayhem. When it ended, 34 people had been killed, nine hundred injured, some 3,500 arrested, and property destruction was estimated at $46 million, making the Watts riot the worst in American history.

The ascending black militancy emboldened blacks with confidence to unleash their long-contained anger at law enforcement officials. Inner-city residents, enraged and frustrated with police brutality, continued to riot and even began to join groups such as the Black Panthers, with the sole intention of driving from their neighborhoods the oppressive white police officers. Eventually, some blacks went from rioting to even murdering those white officers who were reputed to be particularly racist and brutal. This, some blacks did, while shouting at the officers such epithets as “honky” and “pig.”

Rioting continued through 1966 and 1967, in cities such as Atlanta, San Francisco, Baltimore, Newark, Chicago, and Brooklyn. Many agree, however, that it was worst of all in Detroit. Here, numbers of blacks had secured jobs as automobile assembly line workers, and a black middle class was burgeoning and aspiring toward “the good life.” However, for those blacks that were not experiencing such upward mobility, life was just as bad for them as it was for blacks in Watts and Harlem. When Detroit white police officers murdered a black pimp and brutally shut up an illegal bar during a liquor raid, black residents rioted with explosive anger. So egregious was the Detroit riot that the city became one of the first municipalities from which whites began to move out, in a manner indicative of “white flight.” Apparently, the riot seemed threatening enough to portend the burning down of white neighborhoods as well. To this day, as a result of these riots, urban areas such as Detroit, Newark, and Baltimore have a white population of less than 40 percent. Likewise, these cities evince some of the worst living conditions for blacks anywhere in the United States.

Rioting again took place in April 1968, after Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, allegedly, by white supremacist, James Earl Ray. On this occasion, outbreaks erupted simultaneously in every major metropolis. The cities suffering the worst damage, however, included Chicago, Cleveland, and Washington, D.C. A year prior to this tumult, in 1967, President Johnson had launched the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. The commission’s final report called for major reforms in employment practices and for public assistance to be targeted to black communities everywhere. Thus, an alarm was sounded, alerting its citizens that the United States was rapidly moving toward separate and unequal white and black societies.

With the onset and implementation of Affirmative Action, there came about the hiring of more black police officers in every major city. Today, blacks make up a majority of the police departments in municipalities such as Baltimore, Washington, New Orleans, Atlanta, Newark, and Detroit. While many social observers speak favorably of this development, many others criticize the hiring of these officers as a method of appeasement and a tokenistic cloak for the racism entrenched within law enforcement. Cultural analysts agree, however, that employment discrimination, while still in existence, is no where near the levels at which it was prior to 1955. The abuse of illegal drugs remains a blight in poor black neighborhoods, but statistics now show that whites and Hispanics are just as likely, if not more so, to experiment with drugs. In summary, the triumphs won during the civil-rights struggle wrought improvements across the urban landscape, enhancing the quality of life in tremendous ways. Yet, much work remains to be done before authentic equality and racial harmony become the reality in America.

Black power (1966)

During the period that Dr. King found himself at odds with factions of the Democratic Party, he was, likewise, confronted with challenges from within the Civil Rights Movement. This was an ideological and methodological challenge, and it concerned two key tenets upon which the movement was philosophically based: integración Y non-violence. A number of SNCC’s and CORE’s black activists had chafed for some time at the influence wielded by the civil rights organizations’ white advisors and the disproportionate attention given to the slayings of white civil rights workers, while the murders of black workers often went virtually unnoticed.

Stokely Carmichael, who became the leader of SNCC in 1966, was one of the earliest and most articulate spokespersons for what became known as the “Black Power” movement. He invoked the phrase Black Power—coined by activist and organizer Willie Ricks—in Greenwood, Mississippi on June 17, 1966. Carmichael subsequently committed himself to the goal of taking Black Power thought and practice to the next level. He urged black community members to arm and ready themselves for confrontations with the white supremacist group known as the Ku Klux Klan. Carmichael was convinced that armed self-defense was the only way to ever rid black communities of Klan-led terrorism. Internalizing and acting on this thought, several blacks, armed and prepared to die, confronted the local Klansmen. The result was the cessation of Klan activity in their communities.

As they acted on the tenets of Black Power thought, practitioners found themselves experiencing a new sense pride and identity. As a result of this increasing comfort with their own cultural imprint, numbers of blacks now insisted that America no longer refer to them as “Negroes” but as “Afro-Americans.” Up until the mid-1960s, blacks had valued the ideas of dressing similarly to whites and of chemically straightening their hair. As a consequence of renewed pride in their African heritage, blacks began wearing loosely fitting Dashikis, which were multi-colored African garments. They also began to sport their hair in its thickly grown, natural state, which they dubbed the “Afro.” This hairstyle remained vastly popular until the late 1970s.

It was the Black Panther Party, however, that gave Black Power ideas and practices their broadest public platform. Founded in Oakland, California in 1966, the Black Panthers adhered to Marxism-Leninism and to the ideology stated by Malcolm X, advocating a “by-any-means necessary” approach to eliminating racial inequality. The Panthers set as their top priority the extirpation of police brutality from black neighborhoods. Toward this goal, they aimed a ten-point plan. Their official dress code mandated leather jackets, berets, light blue shirts, and the Afro hairstyle. Among blacks, the Panthers are most vividly remembered for setting up free breakfast programs; referring to white police officers as “pigs”; proudly and defiantly displaying shotguns; popularizing the raised-fist, black-power salute; and regularly declaring the slogan: “Power to the people!”

Inside America’s prison walls, Black Power thought found another platform. In 1966, George Jackson formed the Black Guerrilla Family at the California prison of San Quentin. The stated goal of this group was to overthrow the prison system in general and “America’s white-run government as a whole.” The group also preached the general hatred of all whites and Jews. In 1970 members of this group displayed their ruthlessness after a white prison guard was found not guilty for his shooting of three black inmates from the prison tower. That guard was later found murdered, his body hacked into pieces. By this act, Black Guerrilla Family members sent throughout the prison their message of how savagely serious they are. This group also masterminded the 1971 Attica riot in New York, which led to an inmate takeover of the Attica prison. To this day, the Black Guerrilla Family is deemed as one of the most dreaded and infamous advocates of Black Power within America’s so-called “prison culture.”

Also in 1968, Olympic gold medalist Tommie Smith and Olympic bronze medalist John Carlos, while being awarded their respective medals during the podium ceremony at the 1968 Summer Olympics, each donned human rights badges, and simultaneously raised a black-gloved fist in the Black-Power salute. In response, Smith and Carlos were immediately ejected from the games by the United States Olympic Committee (USOC). Subsequently, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) slapped the duo with permanent lifetime bans. The Black Power movement, however, had now been given a fleeting spotlight, on the stage of live, international television.

Martin Luther King, Jr., himself, was never comfortable with the “Black Power” thrust. To him, the phrase was “an unfortunate choice of words for a slogan.”[9] While he attributed to the Black Power surge some meritorious attributes, King ultimately concluded:

Nevertheless, in spite of the positive aspects of Black Power, which are compatible with what we have sought to do in the civil rights movement all along sin the slogan, its negative values, I believe, prevent it from having the substance and program to become the basic strategy for the civil rights movement in the days ahead….Beneath all the satisfaction of a gratifying slogan, Black Power is a nihilistic philosophy born out of the conviction that the Negro can’t win. It is, at bottom, the view that American society is so hopelessly corrupt and enmeshed in evil that there is no possibility of salvation from within. Although this thinking is understandable as a response to a white power structure that never completely committed itself to true equality for the Negro, and a die-hard mentality that sought to shut all windows and doors against the winds of change, it nonetheless carries the seeds of its own doom.[10]

Meanwhile, in full disagreement with King, SNCC activists began embracing the “right to self-defense” as the proper response to attacks from white authorities. They booed King for continuing to advocate non-violence, and they deemed him as out of touch with the shifting times. Thus, the Civil Rights Movement experienced an ideological split, akin to the cleavage that had occurred among blacks at the time that W. E. B. Du Bois had attacked the philosophy and methods of Booker T. Washington.

When King was assassinated in 1968, Stokely Carmichael fulminated that whites had murdered the one person who would have prevented the flagrant rioting and gratuitous torching of major cities, and that blacks would now burn every major metropolis to the ground. In every key municipality from Boston to San Francisco, race riots flared up, both within, and in proximity to, black localities. And in some cases, the resulting “White Flight” left blacks in urban devastation, squalor, and blight of their own making, as the wealth required for rebuilding and renewal was unavailable. In 1968 America saw clearly that the glorious and amazing achievements of the Civil Rights Movement notwithstanding, in order to find additional, still-badly-needed answers, thinking people would be forced to yet look elsewhere.

Memphis and the Poor People’s March (1968)

Rev. James Lawson invited King to Memphis, Tennessee, in March 1968 to support a strike by sanitation workers, who had launched a campaign for the recognition of their union representation, after the accidental, on-the-job deaths of two workers. On April 4, 1968, a day after delivering his famous “Mountaintop” address at Lawson’s church, King was assassinated. Riots detonated in over 110 cities as blacks grabbed their guns, determined to wage war in response to the death of the twentieth century’s icon of peace and nonviolence.

Dr. King was succeeded as the head of the SCLC by the Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy. He attempted to carry forth King’s plan for a Poor People’s March, which would have united blacks and whites in a campaign for fundamental changes in America’s social and economic structures. The march went forward under Abernathy’s plainspoken leadership, but is widely regarded by historians and cultural analysts as a failure.

Future implications

Today’s civil rights establishment strives to uphold the noble legacy imparted by the great leaders of the movement’s most turbulent years. More recently some have begun to question the relevance of the NAACP, the Urban League, the SCLC, and other organizations that arose with methods appropriate to the original time and setting.

These challenges notwithstanding, the Civil Rights Movement of 1955-1968 remains one of the most dramatic phenomena in history. The prophetic roles played by the movement’s Christian leaders were courageous and visionary. Key players of the Civil Rights movement drew from the Bible, the teachings of Jesus, and the teachings of Mohandas Gandhi. They reminded America and the world of a value system rooted in clearly defined norms of “right” and “wrong,” and even more importantly were committed to putting these ideals put into practice.

Veja também

Notas

- ↑ John F. Kennedy, “Radio and Television Report to the American People on Civil Rights,” June 11, 1963. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ↑ Medgar Wiley Evers, 1925-1963 Medgar Evers College. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ↑ 3.03.1 Steven Kasher, The Civil Rights Movement: A Photographic History, 1954-68 (Abbeville Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0789201232)

- ↑ Martin Luther King – Acceptance Speech. Nobel Foundation. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ↑ 5.05,1 Quoted in Stephen B. Oates, Let the Trumpet Sound: A Life of Martin Luther King, Jr (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1994, ISBN 006092473X), 345.

- ↑ Robert M. Goldman, H-Net Review: Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ↑ Oates, 455.

- ↑ PBS, From Swastika to Jim Crow. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- ↑ Martin Luther King, Jr., Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? (Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1968, ISBN 0807005711), 29.

- ↑ King, 44.

Referências

- Branch, Taylor. At Canaan’s Edge: America in the King Years, 1965-1968. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 068485712X

- Branch, Taylor. Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1954-1963. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988. ISBN 0671460978

- Branch, Taylor. Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years, 1963-1965. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998. ISBN 0684808196

- Breitman, George, Herman Porter, and Baxter Smith. The Assassination of Malcolm X. New York: Pathfinder Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0873486323

- Foner, Eric. Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction. New York: Vintage Books, 2006. ISBN 0375702741

- Carson, Clayborne. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960’s. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980. ISBN 0374523568

- Carson, Clayborne, David J. Garrow, Bill Kovach, and Carol Polsgrove (eds.). Reporting Civil Rights: American Journalism 1941-1963 New York: Library of America, 2003. ISBN 978-1931082280

- Carson, Clayborne, David J. Garrow, Bill Kovach, and Carol Polsgrove (eds.). Reporting Civil Rights: American Journalism 1963-1973. New York: Library of America, 2003. ISBN 978-1931082297

- Garrow, David J. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. New York: William Morrow, 1986. ISBN 0688047947

- Garrow, David J. The FBI and Martin Luther King. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006. ISBN 0300087314

- Horne, Gerald. The Fire This Time: The Watts Uprising and the 1960’s. Da Capo Press, 1997. ISBN 0306807920

- Kasher, Steven. The Civil Rights Movement: A Photographic History, 1954-68. Abbeville Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0789201232

- King, Jr., Martin Luther. Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 1968. ISBN 0807005711

- Kirk, John A. Martin Luther King, Jr. London: Longman, 2005. ISBN 0582414318

- Kirk, John A. Redefining the Color Line: Black Activism in Little Rock, Arkansas, 1940-1970. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press, 2002. ISBN 081302496X

- Kousser, J. Morgan. “The Supreme Court And The Undoing of the Second Reconstruction.” National Forum 80(2) (Spring 2000). Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- Malcolm X (with the assistance of Alex Haley). The Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York: Random House, 1965. ISBN 0345350685

- Marable, Manning. Race, Reform and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction in Black America, 1945-1982. University Press of Mississippi, 1984. ISBN 0878052259

- McAdam, Doug. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930-1970. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 1982

- Minchin, Timothy J. Hiring the Black Worker: The Racial Integration of the Southern Textile Industry, 1960-1980. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1999. ISBN 0807824704

- Oates, Stephen B. Let the Trumpet Sound: A Life of Martin Luther King, Jr. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 1994. ISBN 006092473X

- Westheider, James Edward. “My Fear is for You”: African Americans, Racism, and the Vietnam War. University of Cincinnati, 1993.

links externos

Todos os links foram recuperados em 23 de novembro de 2019.

Créditos

New World Encyclopedia escritores e editores reescreveram e completaram o Wikipedia Artigo

de acordo com New World Encyclopedia standards. Este artigo é regido pelos termos da licença Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 (CC-by-sa), que pode ser usada e divulgada com a devida atribuição. O crédito é devido nos termos desta licença, que pode referir-se a ambos New World Encyclopedia colaboradores e colaboradores voluntários altruístas da Fundação Wikimedia. Para citar este artigo, clique aqui para obter uma lista de formatos de citação aceitáveis. Os pesquisadores podem acessar a história das contribuições wikipedistas anteriores aqui:

O histórico deste item desde que foi importado para New World Encyclopedia:

Nota: Algumas restrições podem ser aplicadas ao uso de imagens individuais que são licenciadas separadamente.

[ad_2]

Traduzido de Enciclopédia do Novo Mundo/a>

Source link